Hokusai and Hiroshige:

Great Japanese Prints from

the James A. Michener Collection

at the Asian Art Museum.

From The UCSF Weekly,

September 1999

published in Two Parts, one week apart.

by John

Graham

This show provides a once-in-a lifetime opportunity to see the largest

and best preserved collection of ukiyo-e woodblock prints outside

Japan. The prints will be shown in two separate exhibits, one featuring

Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849), from Sept. 23 through Nov. 15, and

the other featuring Utagawa Hiroshige (1786-1864), beginning Nov.

21 and running until Jan. 17, 1999.

James Michener, known for his giant popular novels, wrote

solidly on the subject of Japanese art in The Floating World (1954)

and Japanese Prints (1959). During this time he picked up two well-kept

collections for his archive--a Mrs. Georgia Forman actually willed

her collection to Michener because she was so impressed with his interest

in this peculiar Japanese craft. Michener, who died last year at 90,

had gradually given the prints to the Honolulu Academy of Arts. It

is there that the prints reside, essentially kept under lock and key.

We are very fortunate to see the collection out in the open.

With the commercial production of these prints during

Japan’s Edo period (1615-1868), and the subsequent recognition

of them in the West--including this very exhibit--you are witness

to art history appreciation in the making

Katsushika Hokusai, whose work comprises the first wave of the exhibit,

was a character of extremes. A master who changed the face of woodblock

printing, Hokusai was reputed to have changed residences around 90

times in his life-sometimes twice a day--as well as changing his name

constantly, because all of it would add up to his being a better artist.

His most dazzling work is said to have been produced in the 1830s,

when he was in his 70s. In his last days, he said he needed 10 more

years to get it just right.

The exhibit will show the entirety of Hokusai’s widely

acclaimed "Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji," created between

1829 and 1833. (The series is unnumbered and undated.) One of the

"Thirty-six Views" features the ubiquitous "Great Wave,"

Hokusai’s most recognizable print. Also part of the exhibit is

his interpretation of famed Japanese and Chinese poems--a tradition

to be approached by all fine Japanese artists of the time--in two

series, "One Hundred Poems Explained by the Nurse," and

"Imagery of the Poets." The latter series, notes the catalog,

is so rare that only the Michener collection is known to have all

10 images.

The leaders of Japan during the Edo period attempted to

protect the culture by cutting it off from the outside world. Only

the Chinese and Dutch were allowed in for matters of trade. Yet the

outside trade lines so in dispute were the very channels which changed

the art of Japan (think now of Picasso in wartime Paris, creating

some of his most innovative paintings while under the disapproving

and limiting eyes of the Nazis). In this climate, Dutch copperplate

engravings, censored for their Christian religious content, made it

into Hokusai’s hands.

What crossed borders easily were landscapes. Although

they seemed innocuous, what they held in their four corners was a

form of perspective between the foreground and background which was

unprecedented in Japanese woodblock prints. This is not to diminish

Hokusai or Japanese art’s unique vision. But it suggests that

it is not as insular as one tends to believe.

Politicians and rulers, those rational beings of straight

society who end up creating irrational scenarios, have a tendency

to be trumped when it comes to affairs cultural. It is the artist

here, the supposed irrational being, who finds a judicious way to

connect outside of the body politic. Remember that even the brilliant,

rich blue found in ukiuyo-e prints is called "Prussian

Blue" and was a synthetic ink imported from Berlin in the early

19th century. And to think that Admiral Perry needed a couple of cannons

and boats to get his way.

Towards the end of the 19th century, these Dutch copperplate-inspired

prints, imprinted with German ink, made their way to Europe, influencing

the continent which influenced them. Cargo lines again brought art

to a culture which didn’t know what it was about to be hit with.

One begins to think that "the floating world," which is

the English translation of ukiyo-e, is the world of cargo ships

passing style and craft between cultures.

The French Impressionists openly appreciated the Japanese

prints. Monet built a Japanese-style bridge in his famous garden at

Giverny because he had seen one in a ukiyo-e print. Van Gogh

literally copied two prints into his own paintings simply because

he had been so impressed by them.

The show at the museum is handsomely presented. But it

is important to note that walking around looking at ukiye-o

prints in Western-style frames and glass, hung on walls, is not how

people have generally viewed these pieces.

In Hokusai’s time, the people of prosperous Edo (now

Tokyo) lived lives of literacy, leisure, and even novelty. It was

the world’s largest city at 800,000 people. Hokusai and other

popular artists of the time worked within the complex, industry tryst

of publisher/artist/printer and woodcarver. The public readily bought

these prints as the scenes were local, faces and bridges familiar.

There were no photographs in the world yet. No Life

magazine. This was the four-color process of its day. An average run

would be around 200 prints, with modifications made if they were popular.

It is said the prints sold for "the price of a bowl of noodles."

Still, hanging them in frames on walls is the sleekest

way to show these ethereal works on paper to the greatest number of

people. Blonde, shellacked plywood boards hold much of the exhibit’s

text and description. The tops and bottoms are painted with a mimicking

Prussian blue border, but its use may not actually succeed in this

context. Rather, it proves just how exquisite the ink’s manipulation

must be to work within the realm of an actual ukiyo-e print.

Modern design, animation, illustration, magazine, textiles

and comic book forms owe a tremendous amount to the Japanese woodblock

tradition. After a visit, take a look at what you’re wearing,

or the design of the things in your home; ponder just which hues,

compositions or lines came from the hold of a cargo ship, going one

way or the other, from Katsushika Hokusai.

In conjunction with the exhibits, the museum will be having

related lectures and workshops. Phone 379-8895 or visit www.asianart.org

to find out details.

A highlight of the special events is the exhibit’s

appearance on San Francisco’s own live radio show, West Coast

Live, Saturday Oct. 24, from 10 a.m. to noon. Readers might consider

going to this unusual broadcast, as it is a short walk from campus.

The show will feature Taiko drumming, an interview with the exhibit’s

curator, Yoko Woodson, and Kiriyama Pacific Rim Book Prize finalists.

Tickets are $12 in advance and $14 at the door. Call 664-9500 to order.

Part II

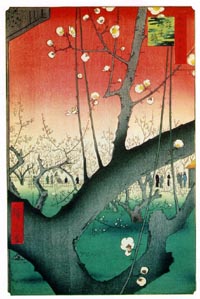

"Hokusai and Hiroshige: Great Japanese Prints from the James

A. Michener Collection" continues in its second phase at Golden

Gate Park’s Asian Art Museum. If you missed the first installment,

featuring the great Katsushika Hokusai (best known for his ubiquitous

"Great Wave"), now is your chance to make it to the show

the second time around featuring Hokusai’s junior at the time,

Utagawa Hiroshige. Although Hokusai was considered to be the more

"powerful" and influential printmaker, it is Hiroshige who

is perhaps the more complex visual artist.

Brief History

Known as ukiyo-e or "floating world" prints, these

elaborately designed and produced artworks on paper were produced

by 10 to 20 separate color runs, which would be virtually unaffordable

from a commercial standpoint today. Enjoyed by average citizens in

18th and 19th century Japan, and costing "the price of a bowl

of noodles," ukiyo-e featured thousands of images of familiar

bridges, mountains, people and birds.

Part of a Japanese cultural industry, linked to Chinese

painting traditions and later influenced by Dutch copperplate engravings,

the prints themselves made it back to Europe in the late 19th century

as simple wrapping paper. It was at this time, when Japan began to

open up both culturally and commercially, that the likes of Vincent

Van Gogh and Claude Monet found their own artistic inspiration in

ukiyo-e. Arguably, the graphic design of woodblock prints was

so far ahead of its time that we can consider the lines and color

of modern animation, comic book design, and high fashion textile as

descendants of ukiyo-e prints. Even popular trends in contemporary

tattooing reflect woodblock’s graphic sensibility.

The Artist

At the age of 10, Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858) inherited his father’s

samurai position as fire brigade warden in Edo (now Tokyo). He apprenticed

himself to an older ukiyo-e artist around 1811. By 1822, at

the age of 25, Hiroshige had retired from his position on the fire

brigade to pursue art full-time. His main interest would be landscapes,

which at the time occupied a very small niche in the woodblock genre.

Within 10 years, though, Hiroshige would master and develop the depiction

of river, mountain and tree--and the people living with them--as an

important genre in the woodblock tradition.

The Series

Just as Hokusai became known for his series "Thirty-six Views

of Mt. Fuji," which included his famous "Great Wave,"

Hiroshige is most famous for the series "Fifty-three Stations

of the Tokaido Road" and "One Hundred Famous Views of Edo."

The Tokaido Road ("eastern sea road") was the

main road between Edo and Kyoto and traversed in its day by many travelers

of different social classes. So its route was well known. In fact,

the Tokaido Road has remained an integral part of Japanese travel.

Today the journey is made by bullet train, a brisk two-and-a-half

hours of travel versus the fourteen days it took for the average 18th-

or 19th-century Japanese commoner on foot.

What is immediately intimate about Hiroshige’s views

of the Tokaido Road is the local, colloquial value of the imagery

which any traveler of the Pacific Coast Highway might identify with.

In "The Famous Teahouse at Mariko, Station 21," a sign in

the teahouse advertises its "famous yam soup," evoking,

perhaps, for the modern viewer an advertisement for "Pearl’s

Famous Cheesemelt" found only in some small lodge in Nepenthe

along the Big Sur coast. This motif of popular foods plays a part

in many of the Tokaido Road prints and would likely interest anyone

studying the day-to-day culture of Japan at the time.

The Social Order

So much is made of the landscape and its icons in Hiroshige’s

work that the theme of social order may be overlooked. The manner

of dress worn by the inhabitants of the prints and their literal social

position to one another--e.g., whose feet actually touch the ground--is

so meticulously recorded that Hiroshige the artist inadvertantly becomes

Hiroshige the anthropologist. Indeed, class division is inseparable

from Hiroshige’s representation of people. While the Japanese

woodblock print may represent a "floating world," its inhabitants

are anything but floating, attuned as they are to a fixed, social

path. But tracking the hierarchies becomes part of the game.

The museum should be commended for its highly informative

wall boards denoting the monetary values related to the day’s

travel. For example, the guide to compute a porter’s worth for

crossing a waterway--with the princess and her things on his back,

of course (now that’s literal social position)--is both remarkable

and practical (water up to the shoulder costing more than water up

to the ankles, and points in between). One gets the sense of a functioning

society’s socioeconomic parlance just slightly different from

our own--but just slightly.

The Visual Order

With all due respect to Mr. Hokusai, the first master presented in

the series, I am compelled to nominate Hiroshige as his better with

regards to composition. Look at "Processional Standard-bearers

at Nihon Bridge." One could take a whole month copying the piece

line for line without capturing its subtleties. This demonstrates

a superior skill level on the part of the artist, as well as his carver

and printer. While Hokusai emphasized color and innovation-and Hiroshige

owes a great debt to him for this-Hokusai simply did not render such

an intricate and enjoyable ensemble of people and things.

Now take a look at "The Lake at Hakone." With

its sweeping, tall cliff and short, cursive, back-peddling trees,

the left to right lines are a stroke pattern evoking their own syntax.

Peopleless, "The Lake at Hakone," like many woodblock landscapes,

provides a fine argument for a common Pacific Rim stroke and line

which is currently emerging in contemporary West Coast artists. These

could be California cliffs, populated with chaparral, manzanita and

coastal live oak.

All of this is not to be received with simple, constant

awe. The viewer may have questions and doubts. If an artist should

be noted for their line, for the "shorthand" they have developed

for reality (an artist is not a camera!), then Hiroshige’s nearly

mnemonic values for what is a cliff, a mountain, or a tree should

be commended. What is odd is his choice for the representation of

smoke (see "Karuizuwa Station"). Where are the evolved cursive

lines that are Hiroshige’s voice? Would reiterating these lines-already

used for other icons in his work-create graphic conflict? It leaves

one wondering. But how can I say that Hiroshige’s depiction of

smoke is beneath his talent-after all, who am I to question a Master?

Hiroshige will be at the Asian Art Museum through January 17. The

museum is located in the DeYoung Museum in Golden Gate park -a short

walk from campus. Tickets for the show are $9.50, which is $2.50 more

than the regular admission price. Phone 379-8895 or visit www.asianart.org

to find out details.