Free Energy 101:

Bruce Depalma and the N Machine

California Dreaming

This piece originally appeared in

Guardian Stewardship Editon's "Bohemian Highways: Art & Culture Abide

Then Divide Along the California Coast," 2015

BY JOHN GRAHAM

“One day man will connect his apparatus to the very wheelwork of the universe . . . and the very forces that motivate the planets in their orbits and cause them to rotate will rotate his own machinery.”

—Nikola Tesla

In 1981, my first summer away at college, I met a mad scientist who had a perpetual motion machine.

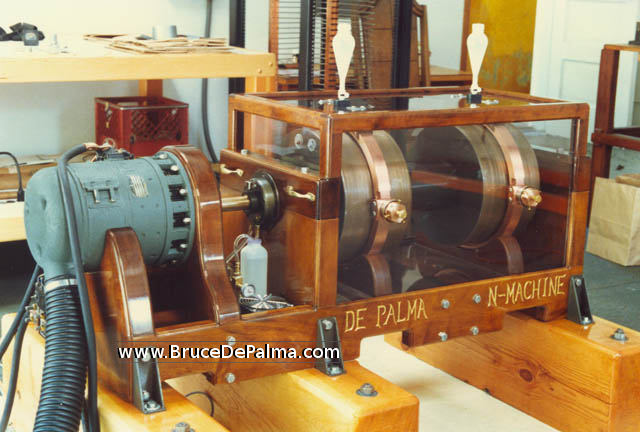

No fooling. I saw it in his garage in Montecito, California, off of Highway 101, along the cliffs next to the Biltmore Hotel. It had an electric motor the size of a basketball attached to a spinning cylindrical magnet of equal capacity. It was slick, shiny, heavy, sprouting wires, attached to gauges and called the “N-Machine.” Well bred, the contraption allegedly produced more energy than it used, pulling stuff out of thin air—its success was going to change the world!

Or so said the mad scientist.

His name was Bruce Depalma, a 1958 graduate of MIT, and the brother of Brian Depalma, the filmmaker, who, it turns out, had gotten his start in science as well before turning to filmmaking. In high school, young Brian even picked up a local award for a piece called “An Analog Computer to Solve Differential Equations.”

Less Click and Clack and more Cain and Abel, the two brothers disparaged each other. Bruce was not impressed with his brother’s movies (“misogynist!”) and Brian seemed unimpressed with his mad scientist brother. They hadn’t talked in years.

To be fair, Bruce Depalma wasn’t really a mad scientist. He preferred to be known as an inventor and keen to avoid any hairy moniker that put mad and scientist in the same sentence. Indeed, Dr. Depalma described the N-Machine and his requisite theories in a paper called “On the Possibility of Extraction of Electrical Energy Directly From Space.” [FN1]

Top that, Brian.

At his core, Bruce Depalma was a research scientist, visionary and oddball (it takes an oddball) with the right mix of modesty and guru hijinks to convince people to separate themselves from their capital to change the world. He did, however, have a few moneymaking ideas of his own. One was a magnetic donut he “invented” that, he claimed, purified all liquids poured through the hole—even the afternoon gin n’ tonics we indulged in went through the donut hole. He reckoned sales of the magnetic donut could support the development of the N-Machine.

convince (ken-vins’), v.t. [< L. < com-, intens. + vincere, to conquer], to persuade by argument or evidence; overcome the doubts of; cause to feel certain.

Although he had managed to set himself up in some pretty tight digs, Bruce Depalma wore simple, single color T-shirts, tennis shoes and shorts—his Mao suit. Yet when it came time to give a paper, the good doctor’s traditional back East self kicked in and he would wear a suit, vest and tie. A good sense of the Depalma skill set can be found on You Tube where he’s seen lecturing and discussing free energy with colleagues like Paramahamsa Tewari and Adam Trombly, all gentlemen N-Machiners nodding to one another with aplomb.

Bruce Depalma had always been on and smart. He needed to be. He was marked from birth.

Born in 1935, he was tallish, both lean and dough boy soft at the same time, with long, thin straight hair behind the ears, that he cut only years later—plus, as I remember, a set of webbed toes on each foot.

Then, for a creature of Italian descent, he had clear, light skin, but on the right side of his forehead, from the eyebrow to his scalp, a Gorbachavean birth mark resided. Gorbachav before there was Gorbachav. Then, after some conversation, you would see that there was another aberration, a flaw in the right eye and a scar that was hidden by the birthmark. It turned out that his iris had been damaged and face scarred in an outrageous wreck.

Ripping along one afternoon on a winding road in a New England forest, the younger Depalma, in love with good mechanics and a swell sports car, ran into a mature buck whose rack came through the windshield, cutting the animal in half as it diced Depalma’s face. Eventually he woke up in the hospital, alive. Fate and physics—of the autobahn kind—having marked him again.

Then there was the laugh.

It was the same kind of laugh one gets from the Dalai Lama, unleashed at the right moment, both undermining the tension in the room as well as convincing you that everything was just fine. You don’t follow the science? Bruce Depalma was going to make you feel like you did—by laughing the hard part away.

Often he would exclaim that the energy in the room was off and have all of us sit still, with our palms up, hands in our laps for a few minutes. This would be followed by another laugh that ended the pocket séance we had fallen spell to. It was the con in his convincing and it was not always unpleasant, especially when attached to cheery smile.

“DePalma may have been right in that there is indeed a situation here whereby energy is being obtained from a previously unknown and unexplained source. This is a conclusion that most scientists and engineers would reject out of hand as being a violation of accepted laws of physics and if true has incredible implications.”

—Robert Kincheloe,

Professor of Electrical Engineering (Emeritus),

Stanford University [FN2]

While making sure to not have mad scientist uttered anywhere near him, Depalma was also intent on having the N Machine not referred to as a perpetual motion machine. In his words:

“The perpetual motion machine is only supposed to run itself. It could never put out five times more power than is put into it. Perpetual motion schemes used conventional energy sources, whereas the N machine is a new way of extracting energy from space.” [FN3]

His machine—essentially a magnetized flywheel, of homopolar design (like I know what that means)—was a way to take energy from space, latent energy that has always been there but only lately surmised. From Depalma’s perspective, burning gasoline, lit candles, even sticks being rubbed together, were mere physical antennas that pulled energy from space. He referred to this as “free energy,” which held within its utterance the kind of Bohemian, Hippy perspective that was popular at the time.

Having studied gyroscopes early on, Depalma was big on what happens to an object when it rotates versus standing still. That is, does a rotating object somehow pull energy out of space that can be bridled to run man’s machines, eliminating the kinds of waste associated with coal, oil and the like? If it smells like Tesla, then it runs like Tesla. Long before there were electric cars putt putt putting away on a charge further up the road, there was Bruce DePalma and the N-machine pulling free energy out of thin air from spinning magnets.

The summer I met him, and in the next few years, as I made my way through school, I would stop in to Depalma’s place on a weekend afternoon and hang out. One would sit in a chair to the side of his large desk and listen to him talk, with music on his fancy hi-fi, as he deconstructed your world, telling you that everything you had learned was a myth. After you would leave a session with him, driving back up 101, you would wonder if you should take the red pill or the blue pill? It was disconcerting, risky. Maybe I didn’t want my world to change that much—maybe I didn’t want an N-Machine. How was I to have fun with all this new information?

How was I to get laid?

Still, Depalma was fun if you wanted to soak it in, even with the exotic formalities he exacted. Upon visiting his mini rented estate—to even enter the space hatch--you had to wash your hands, remove your shoes and let down your guard, which usually meant closing your eyes and holding your hands at your sides for a minute or so as the scent of Agree shampoo filled your senses.

Agree shampoo? Did my sister live here?

It seemed an eccentric entrance fee. But Bruce Depalma was likely the cleanest clean freak you had ever met. I have never known a person who had so many things in order. The refrigerator had perfectly stacked TV dinners, white walls with extreme key light like a lost shot from a Kubrick film. The freezer and cupboards were the same, each can precisely set apart from the other. Stereo electric cords were snaked across the carpet in meticulous undulations. Even the trash was washed and stacked neatly.

These were the standards, discipline onboard the good ship Depalma. Things like the Agree shampoo and TV dinners were the cheap, nerdy bits of his life. There was nothing New Age to Depalma’s taste in food. He was, oddly, strictly, meat and potatoes. A trip for a summer lunch on Coast Village Road was a hamburger in hand and fries to the right as if a late 1940s early teen were going over his sci-fi magazine with a fantasy meal.

Then there was drink. He loved to drink, passing cheap sparkling wine or gin through one of his magnetic donuts. With the laugh going, he would pass around a fair amount of high-grade marijuana in a wooden pipe. It felt as if you were trepanned around him. It was easy to overindulge as a passenger, where the waft of Agree shampoo mixed with the sweet smell of frankincense cannabis. We all went through the donut hole with Depalma.

One afternoon, Bruce invited me down to his to place to watch him run the machine. He had a few ex-students from MIT days who came around to help with the device. They had, in fact, built this particular one so they knew every nut and bolt.

We were close to the beach, but still within earshot of the freeway. You could hear the train go by in between. Depalma kept tight security and wanted me inside while they ran the contrivance. So I stood to one corner of the old car garage as they primed it.

The thing was pretty immaculate, all machined silver steel, precise, solid in the well lighted space. They got it going, each in tight conversation with one another, an electric motor whirring ever faster as the seconds went by. They wanted to get the beast going enough that they might measure any energy—free energy—coming out of it.

The machine spun. It got tighter and louder and hot. It arrived at a kind of blur and we wondered how far it would go until POW! It blew, jacking all the electricity out of the room. I was by the door and went off quickly to see. Bruce called, “Don’t. Stay in!” But it was too late. I wandered from around the garage, up the dirt path to the street. Neighbors were wondering what had happened, flowing from their houses, looking about under the cypress trees. They looked at me. I shrugged.

The machine had blown out the whole grid.

I went back down to the garage. I peaked in at the group, working away, Depalma interjecting.

“What happened?” someone asked.

“Well,” I replied. “You ruined everyone’s lunch.”

That was not Bruce Depalma’s first N-Machine.

It was his second. The first machine was “stolen” by Norm Paulsen and the Sunburst community, a local new age collective. They were caught in a kind of late-1970s commune collapse which had Depalma getting fooled and feinted out of ownership. It had become, for the most part, legend by the time I met him. And Paulsen, who had originally brought Depalma out to California to build the first N-Machine in 1978, gave him the money to do it. Well, the money that people had given to Norm Paulsen because he was their leader was given to Bruce Depalma to build an N-Machine. And he did it! Until it all went sideways. No one ever builds an N-Machine and lives happily ever after.

At six foot four inches, Santa Barbara native Norm Paulsen (1929-2006) was a formidable yogi and when he had money to wield could be impressive—he had a 78 foot schooner that was well known around the harbor.

A student of Paramahansa Yogananda (1893-1952)—you’d recognize the photo—Paulsen started Sunburst farms in the 1960s in the mountains above Santa Barbara. It became the third largest community of its kind in the United States, producing and selling organic foods. Kids were known to give their entire inheritance to Norm, going apeshit with everything they had just to belong.

Like Depalma, Norm Paulsen had a few life changing experiences of his own. He claims to have had more than one encounter with a UFO, during which he saw a gizmo onboard the spacecraft that he took to be the aliens’ energy source. Years later he told Depalma that the plans for the N-Machine, when he saw them, were the same plans for the machine he had seen whilst aboard the flying saucer.

It was that insane.

Or visionary, depending on were you were on the seating chart. A near death experience in the early 1960s had Paulsen’s doctors put him in a straight-jacket down the road to Camarillo State Mental Hospital, in Ventura.

Stuck between 101 and Highway 1, near prime Chumash Indian burial land (Pt. Hueneme), Camarillo was the Bellevue of Los Angeles. As a psychiatric institute, it had pedigree, as it was the exterior shot of many movies and TV shows. It institutionalized the likes of Charlie Parker and UCSB professor Raghaven Iyer—both visionaries. It had also been the topic of more than a few pop songs (Frank Zappa, Fear, Ambrosia, even “Hotel California” by the Eagles was said to have been a metanym for Camarillo State Mental Hospital). Today, good fortune and location, location, location have made the Camarillo State Mental Hospital the right spot for California State University, Channel Islands—one of the newest Cal State campuses.

Long story short, the second N-Machine on the property in Montecito was Bruce Depalma’s comeback. He could start his work again—with a new, running device, built to spec, with his guys—up against the frustration of Paulsen’s world, where the great guru’s teachings about discipline and chastity were met with his eventual drug predilection and philandering. Disciples began to sue Paulsen. “I saw him pistol whip a kid on that boat,” a guest from the old days retorted about the big schooner. “It was that crazy back then. Things went nuts!”

As one sat with Bruce Depalma, circa 1982, all of us clenching a magnetized cocktail in the afternoon, you could see the frustration that weighed on him. The notion that a bunch of ne’er-do-wells were standing around looking at the first N-Machine, his machine—the world changing contrivance—not knowing how to work it, was a New Age bummer to him. With muddy hands running over the slick silver top of their hostage, all the commune dwellers could do was eventually cover the thing up with a tarp and go back to pulling carrots out the dirt. Like Drake’s supposed Plate of Brass, one wonders whatever happened to the shiny bit of hardware—did it just eventually disappear, sold off for scrap? Its parts rused away to raise money for other causes—more personal and less conceptual? With Paulsen taking money to pay Depalma, it came off as the conners conning the conners, who were conning the conned. Now the conned were selling off bits of the con for staples as simple as electric bills.

The last few times I visited Depalma, things had changed. He had left his smaller, well lighted Victorian digs and moved next door to a bigger plot. While it seemed more California, with its red tile roof and curly wrought iron grates, the place had no light. It was less Mission style than it was Inquisition Architecture. But the upside was that he had found a new acolyte whom I heard through the door of one of the rooms, pounding away at a set of drums.

“What’s that?” I asked.

Bruce laughed. “Oh, that’s Andrew. He’s mad at his father.”

I saw Bruce Depalma only one time later, when I brought along another professor friend, well tenured, with whom I was putting together an art catalogue.

“Well, what’d you think?” I asked him as we left and drove back up the freeway.

“Your friend doesn’t seem very connected to reality.” This coming from one of the bigger hippy bohos I had met since moving up for school.

Bruce Depalma had sustained my disbelief for a good while. I had a great time listening to him, the Grand Pilot of the N-Machine, magnetized through the donut hole. It was a great perforation of the world I thought I knew. I had learned things. True things. But I had decided not to swallow the pill, whatever color it was.

In 1994, the wandering doctor moved to New Zealand with the kid who was banging the drums behind the door. There was interest in his work down there. He continued to push for Free Energy. But his interest in magnetized spirits was just as strong as before, putting him in the hospital more than once. Finally, in 1997, he blew himself out and bled to death internally. I guess the donut hole doesn’t protect the liver. He was buried near Aukland and apparently remains there to this day.

To make his deletion even more apparent, the two houses he lived in on Channel Drive, along the cliffs—and the properties on either side--were bought by the Beanie Baby magnate Ty Warner. A salesman-inventor himself, Warner tore down the houses, razed the land and in their place built a mansion and its grounds. It is said that he has painted on the ceiling of his bedroom the location of the stars on the day he was born, wrought Sistine Chapel-style above the bed. One wonders the exact coordinates of the spot, as if some greater energy might have led Warner and his architect to the place, drawn by the gravity of an old donut hole.

I leave with one of Depalma’s later letters, from 1992, to one Don Kelly from Space Energy Systems, Clearwater, Florida:

“Yes, I have been threatened for my life. The first threat came from Edgar Mitchell, the astronaut who told me that the Government had said there never was any doubt that the N machine was the Free Energy machine they were looking for, and if I tried anything on my own in California I would have my head blown off. And the CIA warned me via Mitchell that I should not leave the country because I would be kidnapped. This was back in 1980, when these efforts frightened me out of going to Hanover, Germany for Dr. Nieper’s first Gravity Field Energy Conference, which is where P. Tewari brought his N machine from India and got the prize for the most clearly observable Free Energy phenomena to date.”

The letter goes on, the search continues, the energy is free. I’m convinced!

- John Graham

San Francisco, CA

2015

FOOTNOTES

Footnotes to “Free Energy 101: Bruce Depalma and the N Machine, California Dreaming” by John Graham. Many of the sources for this piece have been found on http://brucedepalma.com/ and other related Free Energy sites.]

- “On the Possibility of Extraction of Electrical Energy Directly From Space,” published in the British science journal, Speculations in Science and Technology (Sept 1990, Vol 13 No 4).

- Robert Kincheloe, Professor of Electrical Engineering (Emeritus). Stanford University, from his paper “Homopolar `Free Energy’ Generator Test, presented at the 1986 meeting of the Society for Scientific Exploration (San Francisco, June 21, 1986). Revised February 1, 1987.

- From Depalma’s website, brucedepalma.com

|