|

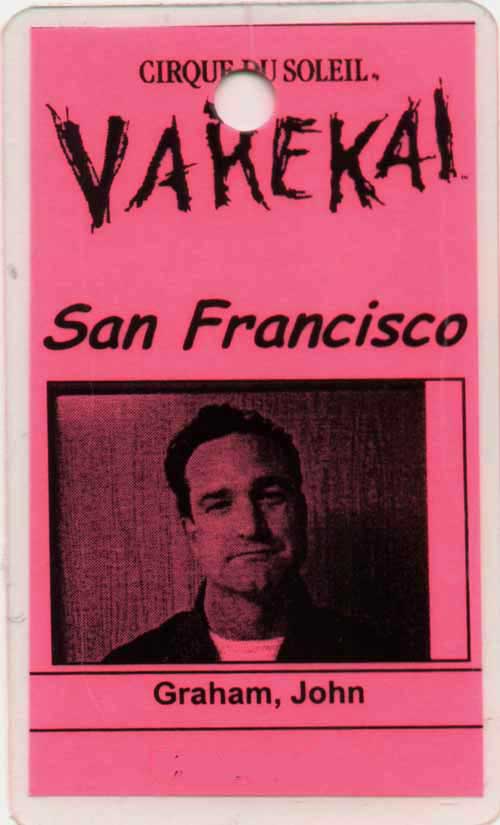

The author's

ID badge worn around

the neck for his circus job.

The Popcorn

Machine

John

Graham

“There are no passengers on spaceship earth.

We are all crew. . . .We become what we behold.

We shape our tools and then our tools shape us.”

— Marshall McLuhan

ASK ME ABOUT

MY MAN Roland spilling the popcorn oil on his shoes. With his handkerchief

he worked the glaze into the leather and made them shine, opening a

whole world of possibilities. The things we used to afford could be

had again. While real shoe wax was momentarily out of the question,

oil from the popcorn machine was going to be just fine.

Working for the circus had us wearing out patent leather

best, as well as jester hats made of felt, carnival shirts, black trousers,

dull photo ID tags slung around the neck. These were the great equalizers

under the tent. As was the popcorn machine.

Mind you, we once had a deal: vice presidents, executive

and administrative assistants, programmers, web masters, Photoshoppers,

coders, sales and marketing people. After our dismissal, the Dot Com

stock options in our top drawers lined our kitties’ litter boxes

for nearly two months. Some had savings. I know I did—a whole coffee

can full of change on the kitchen counter.

I suppose we all had Roland to thank for spilling the popcorn

oil on his shoes. The gaff became a prospect. None of us could afford

anything like mink oil or a shoeshine. We began to circle the oil pool

with rags in our hands, a dozen of us working the gold lubricant into

our dark leathers. How shiny they looked.

I had been cleaning the popcorn machine at the circus for

the last month. The same time last year I was at a university, teaching

and writing a thesis. Now I was digging ditches in a popcorn diorama.

I delineated the predicament. One theory I fell back on

was that conditions had turned me into an ant and the popcorn machine

was my aphid. Rubbing the machine down with a rag produced the sweet

nectar I could live on. It didn’t come directly from the machine

itself—not a polyp of syrup grown out of its stainless steel, or

an offering from its foggy glass—it was the envelope that showed

up in my mail box at home. That is where I could find my nourishment

as the ant I had become.

As I cleaned the popcorn machine, I knew—from years

of smarty pants seminars—that I was facilitating a complete reach-around

in support of Marshall McLuhan’s declaration that all tools were

an extension of our nervous systems, each bringing our desire closer

to a face whose eyes, mouth, ears and nose were waiting. The ape in

me was using a stick to eat termites.

When I first started cleaning the popcorn machine, I couldn’t

see the direct connection between my action and my reward. My movement

within the machine—whole head and shoulders sometimes inside to

tight spots—was indirect tool using. I was not using the machine

to feed myself popcorn. I was doing the cleaning motion for money. It

was the abstraction of the hunter-gatherer conceit: I moved things around

in the popcorn machine, washing it with a rag like a farmer yanking

at teats, a man and his spear walking the bush, accountant with a pen

and ledger. When I stroked the popcorn machine a packet of something

sweet known as my paycheck came out of the postal system in the form

of something known as an envelope in my mail box.

I realized by almost having nothing, newly beat, that the

whole human system was an extension of the collective nervous system.

Big wow. The vagrant, indigent and homeless I passed on my way to this

lame but necessary circus job: they were situated outside of the system

and at few points, if any, did they connect up or plug in. Nothing came

to them in the form of a sweet packet. They stroked no aphids as they

were not in the proximity of any aphids to begin with.

“Where have all the aphids gone?”

I ran my fingers through my pockets.

Each night at Cirque, when everything was cleaned up and

shut down, we rubbed our shiny shoes with popcorn oil and headed out.

People watching us leave the tents were impressed. If it weren’t

for Roland spilling the popcorn oil, none of us would look as good as

we did. It didn’t matter that we didn’t have jobs—not

real jobs (we worked at the circus for heaven’s sake)—at least

our shoes looked fine.

I headed home, on the train each week, to find my sweet

packet waiting in the box for me, just an ant in a colony living the

dream.

With shiny shoes.

—John

Graham

San Francisco, 2007

|