11.

The Cliff

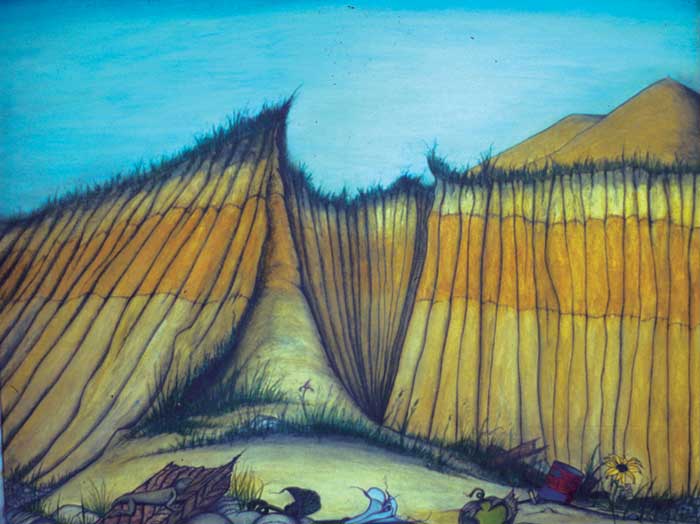

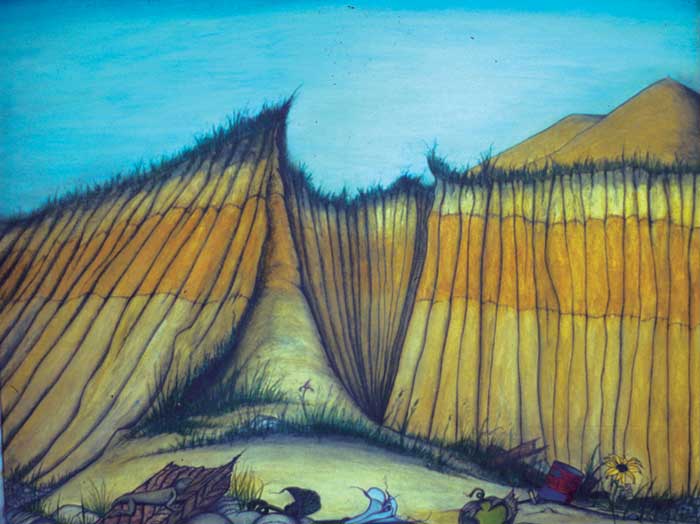

THE CLIFF SAT AT THE EDGE of the canyon like a four-layered cake. Above the top layer, a crown of grass grew like a crop of hair, green against the sky.

The first layer, under the grass crop, was a short charcoal black band of topsoil, made of dead vegetation and the ash of grassfires. Next was a mix of white chalk and yellow limonite, all sedimentary deposits from old ocean bottoms. Then sat a band of hematite, red iron-oxide from a previous world’s alluvial run. Lastly, a taller band of yellow earth sat: diatomaceous and yellowish limonite.

At the bottom of the cliff, where the dust of the four bands fell to the bottom of the ravine, was the detritus of human activity.

There were boards and rusted rebar twisted into the creek cobble. A yellow daisy grew by itself next to a red and rusting can of opened El Fornio Brand Dolphin Meat. In front was a damaged, open-husked tomatillo—green as day—that had fallen off of a truck heading out of town. Up the incline, at the base of the cliff, grew a California Wild Iris, its petals yellow and purple.

Along a splintered, dried mahogany board a blue-belly lizard, a.k.a. Western Fencer, sat, doing push-ups, before he darted into the cobbles.

Datura grew healthy in the late Summer, and not far from the dolphin can lay a bell of the flower, attached to a deep green vine with tobacco-like leaves, the bud of a prickly-laced ball sitting snug up to the part where the leaf and the vine parted. The petals of the datura were white with purple tinges, eight corolla accented and measured the bud at its curled points. It was the host of a religion, for centuries, but nobody noticed the blooming datura sitting by itself in the sun at the bottom of the cliff.

Not now. |