|

Darby worked

for Delfina & Co. The outfit that put people in the water

with El Fornio's famous dolphins. Here he watches over a group

of mothers and their daughters as they ride the dolphins.

I FORGOT TO MENTION

that on the afternoon Serra’s heart was stolen, as we made

our way through the throngs of Old Spanish Day revelers, Janet

and I ran into Darby Hipper.

At first we thought Darby was going to be a likely

accomplice on our journey to the Rusty Pelican, but he was all

business, on his way home after work.

“Just heading back,” he sighed. “Not

really a day I want to stay out. Plus, I’m repainting the

house.” He looked around at the rising mayhem.

“All you do is paint that house,” I told

him.

“Yeah,” he reckoned. “It’s like

the Golden Gate bridge er somethin’—you get to one

end, and it’s time to turn around and start over at the

other.”

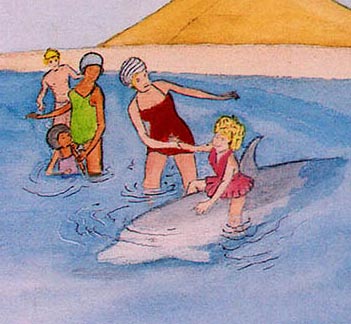

Darb worked out of the harbor, for Delfina &

Co., the “Swim with the Dolphins”

tour group, and both Janet and I could see the salt and sun

of a day’s work had worn him out.

Packages

start at $199. But for $39 you can smell

their fins while you touch their heads.

At twenty-six, looking like a blond-haired Tom Cruise

("great hair without the Scientology," I always said),

Darb was in flip-flops with dirty toes, one bloody and stubbed,

white shorts, worn out red tank top and a Dodgers cap. He had

a black bag slung over his shoulder that he kept adjusting delicately

with two hands supporting the weight at the bottom.

Janet looked him over. “You got something special

in there, Darb?”

He laughed. “Caught me, eh? Check it out.”

Darb took the bag off his shoulder and put it on the ground.

“It washed up the other day.”

He took down the sides and lifted up a tall, two-gallon

jar. Inside a small, hairless animal floated in formaldehyde,

its short nose against the glass and tail curved slightly to

fit in the space. “Targuman found it on the beach near

White Hills yesterday.”

“Of course Targuman did,” I came back.

“He finds all the weird bric a brac.”

“Is it a baby dolphin?” Janet asked.

“A fetus,” Darb nodded. “I think

it’s perfect. Not a mark. It could be the offspring of

a mother killed by locals. Or I’m also thinking a swordfish

might have done her in. They’re starting to run. I

don’t think it’s any of our dolphins.”

I bent over and looked closer at the creature in

the jar. “So this goes right into your collection? Just

like this?”

“Who’s asking? You—or the lawyer?”

“I’m askin’,” Janet said. “Not

the lawyer.”

“Yeah. Into the colleción,” Darb

said, dropping into Spanish. He put the jar back in the bag

and hoisted it over his shoulder, sloshing. “It’s

a keeper, for sure.”

And Darby had quite a collection. Local snakes,

fish, rays, an El Fornio iguana, embryos of vertebrates and

invertebrates—even the heart of a convicted criminal he

had picked up on Ebay—all were nicely held in jars of preservatives

with notations and sourcing. He made no bones about his collecting

hobby, and let anyone come and see the shelves he kept neatly

dusted and tidy. Some had names, as if they were pets, like

“Henry the Green Rock Crab” or Dahlila who was a moray

eel he had bought one day off of a fisherman.

The afternoon he brought her home, Darby wrestled

the muscular beast into a pillowcase, still alive, before convincing

it of its new quarters

Dahlia wasn’t a random name.

The story goes that as Darby forced the moray into

the jar from the sack, Tom Jones was working his way through

a tune on the radio. The sight of the moray in the glass was

encoded with the hook of the jingle and every time he looked

at the eel peering back at him, the song would play in his head.

“That’s Dahlila,” he would say to people, and

the name stuck. “Like the Tom Jones song.”

Janet loved that kind of thing. “One more for

the shelf,” she laughed. And off we were to the Rusty,

leaving Darby as a party mate for another day, which was too

bad. We both liked Darby a lot.

Darby Hipper hadn’t seen either of his parents

for some time. His father had been out of sight since Darb was

six, having garnered permanent residence in Columbia due to

certain commercial ambitions he had developed with the coca

leaf. After the father’s incarceration, his mother, Janis,

brought the boy back from Los Angeles to live with her in El

Fornio.

Janis was fifth generation El Fornio and part of

the graduating class with Elihu Targuman. She remembered Eli

years afterwards, “He was so normal, chess club and the

total dork that would ask you out. And then all of a sudden,

his outsides were the same, but his insides had changed.”

Darby and Janis lived with her parents at the family

house, the sixth lot down at 257 Sardonxy Way. Her older brother

Robert had disappeared years before after a falling out with

their father, Robert, Sr. In 1976, a family friend on a visit

to Spain claimed to have seen Robert, Jr. in the Alhambra.

“He always thought that the Gypies were the

real people of the world,” Janis recounted. “And,

sure, fine. But,” flicking the ash from her cigarette.

“Maybe the Gypsies are something special, but if you aren’t

a real Gypsy, why fake it?”

Her parents lasted another two years, dying just

a month apart. Janis got the house, which had long since been

paid for, and kept her and Darby ankle deep in tuna helper and

quesadillas by working for the Rusty Pelican.

The Rusty

Pelican has been a bar, tavern and restaurant in El Fornio since

1876.

They are known for their Mahi Mahi burgers, Bloody Marys and

great bands.

She

was a pretty good waitress, in a small town way, BLTs, grilled

cheese, tomato soup, local fish specials. She did breakfasts

and lunches, got off work and joined other locals in the business

for a drink at work, then two or three down at the Leathercoat.

Another at the Hungry Tiger, then Safeway where she would pick

up a gallon of Inglenook.

By this time Janis was smoking about a pack of cigarettes

a day (Cool, menthols), eating a spot here and there and putting

away a fair amount of Malibu and diet coke. She had lost a couple

of teeth, but they were molars so no one noticed and what had

been at one time a sweet beach girl figure was becoming more

wiry by the season. After Darb’s father, Janis hooked up

occasionally with one man or another, but they sensed the weakness

in her or lingered to take advantage of it.

Sometimes she wouldn’t come home at all, but

that was much later and Darb would check her room every morning

before he went off to school. He knew he could find Janis at

any number of places along the wharf if he spent the time to

look for her.

“Have you seen Mom? Is she in there?”

Darb would skateboard from joint to joint looking after her.

By

Darby’s freshman year, Janis was hitting forty and life

was catching up. She didn’t work full-time and when she

did shifts could fall apart depending upon how liver weary she

was. Her focus was waning. Darb always thought it was the loss

of one of her front teeth, the right incisor, that was the beginning

of the end.

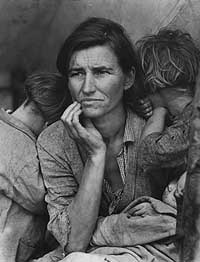

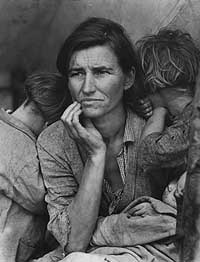

“Hey,” she said one late morning, sitting

at the kitchen counter, having a smoke and a diet coke. “Look

at that,” pointing to a picture in an article in the Sunday

paper. One of Dorothea Lange’s dustbowl women was resting

her face on a wispy hand. Janis laughed, “I made the paper!”

“One

of Dorothea Lange’s dustbowl women

was

resting her face on a wispy hand.

Janis laughed, “I made the paper!”

Then she would rearrange her collection of abalone

shells and driftwood on the kitchen windowsill thinking that

it would bring good luck. “There,” after fifteen minutes

of moving mother-of-pearl and salty wood around, she’d

say, “It’ll be a great week!”

Darby finally went down to city hall one afternoon

and got the forms for Janis to fill out. By going on disability,

with a son who was still a minor, she qualified for a workable

monthly stipend. Darby picked up slack by working for Ed and

Abby Goodman at Mission Petrol with additional shifts at Hang

Dog, the surf shop on the wharf.

At the end of the summer, at the Fiesta parade,

weeks from Darby’s sophomore year, Janis died face down

next to a Bear flag plastic cup, one flip-flop on, one flip-flop

thirty feet from where she had been found in the early morning

by Targuman and the clean-up crew. It was Janet and myself—with

Targuman muttering on the periphery—who told Darby the

news, and he took it pretty well. He knew that his mother had

been suffering and that the life other people had was never

going to be the life she had.

“Janis could have never had another drink,”

Darby knew, “And anyone who met her would still know something

was up.”

To her credit, Janis made it look like a kind of

happiness. “She was the queen of happy hour!” a buddy

from the Rusty crooned at her wake.

“Water,” Darby told Janet the day of the

funeral. “My mom never drank enough water. She heard it

was dirty around here. Best to get your liquids somewhere else.”

“Like the Rusty?” Janet said.

“At least you get your iron,” he followed.

“Janis probably just laid down like she always did. I found

her a few times when I was on my way to work or school. She’d

be asleep right where she was from the night before. I’d

give her money and sit her back up,” he recounted. “That’s

just the way it is. I don’t want anybody thinking it could’ve

been another way. That’s who my mom was. That’s who

my parents were.”

Darby accepted peoples’ foibles and near triumphs.

When he had learned that Targuman was an El Fornio High Moor

alumni, he was immediately accommodating. “Yeah, then he’s

got to know something, right? He’s got to be more than

just a nut, huh?” Darby scratched.

To the average tourist, even fellow citizen, Darby

Hipper seemed like the amiable surfer, which he was, but he

was also a hard working, unsentimental type, keeping the house

he had inherited in total order.

After Janis’ death, he and

Sean the Pelican man repainted the inside and outside completely

white with a slight washed yellow trim and dash of light blue

in the corners. With jobs cobbled together, Darb paid the property

tax and utilities himself—on time and often two months

ahead so that he could concentrate on being in the water.

Janet knew the reason. “He’s a Virgo,”

she’d tell anyone listening. One day she pointed to his

swim trunks. “Just look. His favorite color—white.”

Because he knew the dolphins as much as anyone in

the area, Darb began working for Delfina & Co. the “Swim

With the Dolphins” outfit that had contracted with the

city and county to bring visitors into the bay whose interest

was getting in the water with El Fornio’s famous dolphins.

Darby became a Master Guide by the time he was eighteen, a year

after graduating high school. Through Janet, he became a member

of the Sirenas Island Channel Keepers, the legal arm that defended

the bay against polluters, taking water samples and propping

binoculars up on the cliffs to look for ships and sailors expelling

their shitty ballast wherever they seemed fit.

The poster

for the Moors and Pelicans

homecoming game the year of the big fire.

After Mission Petrol burned down and blew ski high

during what became known as the “Moor

Homecoming Fire,” Darby went full-time with Delfina

& Co. It was a thrill for him putting people in the water

with the animals. But there were the occasional mishaps.

Most people thought of the dolphins as peaceable

animals, and they were—mostly. But last year, a notable

Los Angeles debutante, the daughter of a film producer, came

up for spa treatments, including swimming with the dolphins.

Unfortunately, she lied on the spec sheet about her menses so

when she was put in the water, some of the creatures went wild,

pulling her under, teething her arms and legs, a quick pass

of the teat and thump of a fin against her head. By the time

Darby dragged her out of the sea onto a waiting Zodiac,

the visitor from Beverly Hills was bleeding and crying.

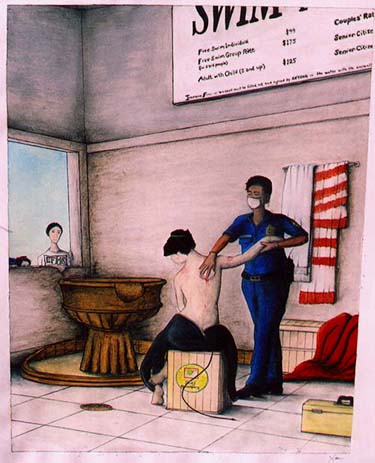

Darby and his crew set her up on shore with the

responding paramedics, one of whom happened to be a local named

Virginia Jefferson. Vee claimed to be the great, great, great

grand daughter of Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings. “Come

on!” she said to unbelievers. “I’ll take the

DNA test any time!”

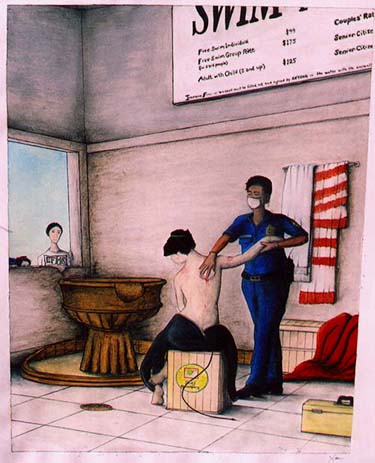

Paramedic Jefferson treated the woman as local kids

and tourists watched the patient, half in shock, seated on a

turned over wooden Aliso-Kennedy

tomatillo crate, wetsuit down to her waist. Vee dabbed the

bite marks with cotton swabs. The patient held an arm up, head

tilted. The gathering crowd gazed upon her in a scene worthy

of Jean-Leon Gerome.

“Paramedic

Jefferson dabbed the bite marks

with cotton swabs. The patient held an

arm up, head tilted as the gathering

crowd gazed upon her . . .”

“That’s

a reality sandwich,” I turned to Darby.

“They’re beautiful animals, but they can

be demons,” Darby replied. “You doing water work down

here for Janet?”

Darb noticed that I held two vials of fluid in my

hand as we walked back up the beach. “Yep, she’s around

here somewhere. We’re supposed to meet up.” I looked

at Darb. “Don’t you have to, you know . . .”

I tilted back at the crowd with the producer’s daughter.

Darb stopped. “Yeah,” he turned. “Reality

bites the sandwich. They’ll expect me to help with the

report. Lame. It always is. It’ll involve the cops, the

county, the city, the owners of Delfina. Everytime something

like this happens someone makes a big deal out of it.”

Darby squinted, looking out over the water. “Maybe the

woman was just a total bitch and the dolphins didn’t like

her. Doesn’t anybody ever consider that?”

|