|

“Junipero

Serra founded the California mission system.

His statues are all over California.

He has streets named after him. His image is on prayer cards

and hundreds of shirts sold in the gift shop at the El Fornio Historical

Society

—that should be enough.

Listen

to voice over artist Tim George

read

the part of Hank Peabody

Visit

Tim George's website to learn more

about his work

www.timgeorgevo.com

Hank Comes to Grips with Serra

from The Reeducation of a Turd Peddler

by John Henry Peabody

“The destruction of a way of life in a foreign land is the

curriculum vitae for canonization? Self-flaggelation and denial of

corporal pleasure by cutting and burning of one’s own flesh with

blade and wax is a prerequisite to sainthood?

I’m going to quote Robert Plant again, `I don’t th’ANK

so!”

— Hank Peabody

Director & Curator

The El Fornio Historical Society

I FINALLY BEGAN

to realize that any romantic obsession with Serra and the Missions was

equivalent to a kind of life cheating. Equating Junipero Serra and the

love of his kow-towing neophytes to sainthood was like kicking your

dog in the teeth or shitting in the well water.

The same people who wanted to rebuild the mission were the

same ones who wanted to sell mission brand salsa and "personalized

sombreros." If they had it their way, Janet and I would be dipping

chips at the Mission El Fornio Grand Opening™ into melted Velveeta

whilst wearing straw hats with “Janet” and “Hank”

embroidered on them . . . All the while the mariachi band would be noodling

away in the background as we wondered how they pulled the event off

without a liquor license. I mean if you’re going to try and bullshit

me, at least do it with a selection of tequilas.

One has to choose their protest. The notion of being politically

correct about Serra’s role as one of the false heroes of California

history seemed as quaint to me as casting him as an epic saint. That

kind of qualifies as a Mexican

Stand Off, doesn’t it?

Rebuild the mission. Don’t rebuild the mission. On

any hot August afternoon, we’d all like our wife to be able to

peruse the gift shop in her white summer dress. The question is, Where

do we want her to be doing the perusing? (And how do you get a wife?)

Hell, I had to find a job in a career path that was hit

or miss to begin with. Even Janet didn’t realized how close, just

a year or two earlier, I came to dressing up like one of Snow White’s

elves just to secure a pay check (SEE: Goleta

Train Museum, my application there).

Weren’t there enough local obsessives who wanted to

flay the chaste Mallorcan as they ran around with placards and bull

horns, calling him out for being mean to the Indians?

Don’t lean on me. I had rent to pay, a PG&E bill,

car insurance, two piles of laundry and about forty Central Coast coprolites

from the Middle Era to classify, diagram and hydrate You’d think

they could fill the ranks of the protestant with one more Birkenstocker

who cared more than me?

You’d think.

I’m fully aware that there will always be mythological

seepage when discussing place—I took that seminar in grad school.

The deal was to figure out where to stand and poke your finger into

the narrative dyke—as it were. So here’s my finger. I’m

holding it out. And this is where I’m poking it.

* * *

Mission Carmel, Monterey, California, Pebble Beach, golf course, Cannery

Row, John Steinbeck, big aquarium, deep bay, 17 mile drive, Asilomar,

Julia Morgan, Mayor Clint Eastwood, John Denver’s plane out of

gas, Rocky Mountain High going into the drink—this was the national

shrine of Father Junipero Serra, born in Mallorca, founder of the California

Missions and subject of the Catholic Church’s canonization process,

pressed in a tin with olive oil, capers and white wine—a pinch

of diatomaceous earth atop. And, oh, yeah, his ticker in a jar of formaldehyde

bouncing around somewheres no one seemed to know.

Founded in 1771, the mission saw Serra, his cohorts and

soldiers, living like Robinson Caruso in thatched huts, holes dug in

the ground and covered with spare ceiling, attempting to plant crops

as if they were in Europe. Like Vikings in Greenland, they were merely

beginning to set the groundwork for their own starvation as the Natives

thrived.

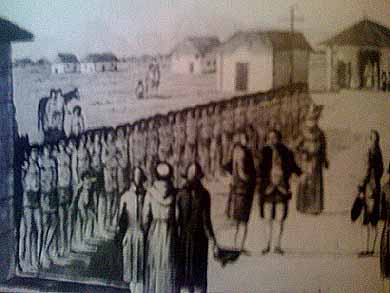

Jean Francois de

La Perouse visits Mission Carmel in 1796. Perouse was Serra and company's

first European visitor. Of his time at the mission settlement, Perouse

wrote, "Sins which are left in Europe to Divine justice are here

punished by irons and stocks

When the Jacques Cousteau of his time—the first European

visitor to the mission—Jean

Francois de La Perouse, came to Monterey on September 14, 1796 aboard

the ships L’Astrolabe and La Boussole, he observed

that the research and development project that was the Spanish empire’s

California mission system was comprised of one padre to nine soldiers,

making a team of two padres and eighteen soldiers per mission.

It was a bad situation all around. Perouse commented that

what was fashioned at the new Spanish settlements was not a shot at

the recreation of a European town, rather an attempt to make the average

person act like they were a committed and chaste disciple of the monastery.

“Sins which are left in Europe to Divine justice,”

Perouse wrote, “are here punished by irons and stocks.”

And to what material end, aside from the spiritual discipline

the padres were exacting, did they strive?

Upon initial contact with the Europeans, the locals were

flush with game and fish and floral gastronomy. Captain

George Vancouver, the explorer from Britain, made mention six years

after Le Perouse’ visit that the settlement did not “indicate

the most remote connection with any European or civilized nation.”

San Francisco’s settlement was “enclosed by a mud mall and

resembling a pound for cattle.” The commandante’s quarters

in San Francisco were equally “without being boarded, paved, or

even reduced to an even surface: the roof was covered with flags and

rushes; the furniture consisted of a very sparing assortment of the

meanest kind.” The commandante’s wife received them “seated

crosslegged on a mat.”

They had turned into literal hippies without comparable

goals, examples of a supposed dominant civilization living like twenty-year

olds in a college town without plumbing, treating longstanding, pretty

well fed and accomplished adults around them like out-of-line pets.

Kinda Taliban.

After San Francisco, Vancouver felt the same of his visit

to Monterey—eight years after Serra’s death, still not a red

tiled roof, bottle of Zinfandel or plate of Nachos to be found. They

lived in “miserable mud huts” with the same “lonely uninteresting

appearance” as the missions to the north.

And this is the qualification to be a saint? This work by

Serra? This set-up? The destruction of a way of life in a foreign land

is the curriculum vitae for canonization? Self-flaggelation and

denial of corporal pleasure by cutting and burning of one’s own

flesh with blade and wax is a prerequisite to sainthood? Divide

or multiply these actions with the three necessary and mysterious miracles

required of a candidate saint and it is hard for one to move forward

in support.

I need a tequila but will hold off—thanks for asking.

Junipero Serra founded the California mission system. His

statues are all over California. He has streets named after him. His

image is on prayer cards and hundreds of shirts sold in the gift

shop at the El Fornio Historical Society—that should be enough.

An earned run average like that merits a substantial amount of introductory

sentences and index entries.

But sainthood calls into question the whole mojo of sainthood

to begin with.

When Serra’s lifelong friend Father

Juan Crespi died on January 1, 1782, he was interred beneath the

sanctuary floor of Mission Carmel (although the stone church wasn’t

even begun until 1793, under the direction of Father

Fermin Lasuen, there is some suggestion that Crespi’s body

was kept in a tossed water heater box in the woods until the church

was completed.).

Serra passed in 1784 and then Lasuen in 1803. The lot of

them are set side by side—Moe, Larry, Curly-style—beneath

the sanctuary floor at the mission.

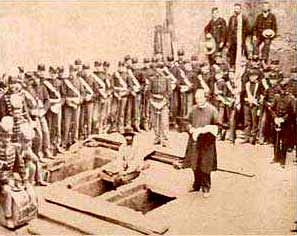

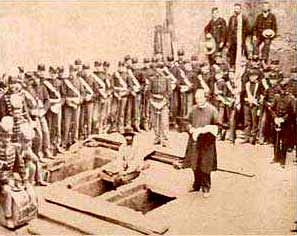

On his road to sainthood, Father Serra has been dug up three

times. In 1856, he was exhumed for confirmation of identity. In 1882,

the trio were undug again,Elevator Shoes this time with a cadre of St. Patrick’s

school cadets brought down from San Francisco. An excellent

Mathew Bradyesque black and white photo of the event shows a well-plumed

drum major, two ladies in their finery, an Indian grave digger (a Fornay

agent, by the way), a man looking like Karl Marx in the back row to

the right, dozens of soldiers, and the priest of the day standing above

the open tombs looking suspiciously like Edgar Allen Poe. (The casual

to serious scholar can make note of these details by obtaining a copy

of the photograph below).

In 1882, Serra,

Crespi and Lasuen were unburied again.

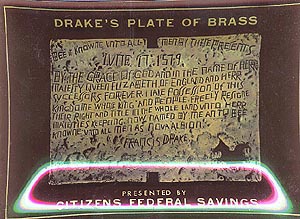

When the modern canonization process was begun, the old

padre was unburied again in 1943. A tribunal of church authorities were

on premise, in 1950, when Dr.

Herbert E. Bolton himself gave testimony to Serra’s role in

California’s history.

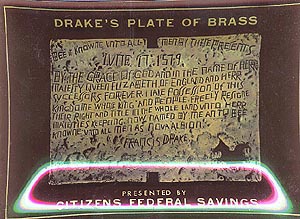

Afterward, Bolton shook hands with the officials and gave each a gift

of a Citizens Federal Bank ashtray commemorating Drake’s

Plate of Brass. (Fifty years later, one of the ashtrays would be

bought by me at an antique stall during “Old Spanish Days”

festival).

Pope John Paul II declared Father Serra “venerable”

in 1985, which meant he was “lovable,” one step closer to

being “huggable,” which finally leads to “cuddily.”

In 1987, John Paul himself visited the mission. Showing

up with a small garden shovel and sun hat, the Pope needed authorities

at Carmel to explain that Father Serra’s body had already been

dug up. His Holy Father was quoted as saying, “Oh, dang” as

his assistant took the little shovel from his hand.

Finally, in 1988, Serra was “beatified,” which

put him right up there with Jack Keroauc and Allen Ginsburg.

Across the meadow, out behind the good father’s mission,

we could all hear the ghostly pant of the occasional neo-phyte as he

knelt, was flogged and made example of. In this way, the missionization

of Alta California—and Father Junipero Serra’s master plan—carried

on without a hitch.

Sort of.

|