|

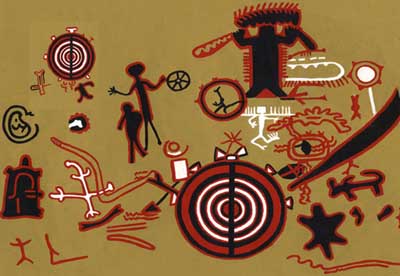

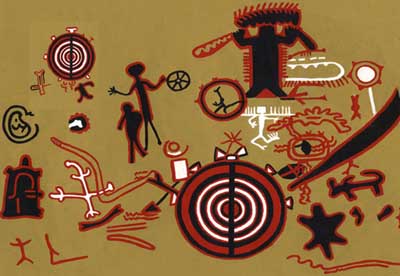

Example of Chumash

pictographs from Cambell Grant's

"The Rock Paintings of the Chumash."

Listen

to voice over artist Tim George

read

the part of Hank Peabody

Visit

Tim George's website to learn more

about his work

www.timgeorgevo.com

A Visit to the Hall of Jars

from The Reeducation of a Turd Peddler

by John Henry Peabody

WHEREIN, UP

IN THE PASS, HANK IS INTRODUCED

TO OTHERS IN THE TRIBE AND SHOWN THE HALL

OF JARS, WHERE SERRA'S HEART SHOULD HAVE

BEEN IF IT HAD NOT GONE MISSING ALL THOSE YEARS.

THEN, A PHONE CALL CHANGES EVERYTHING.

JANET

HUSTLED US up the trail towards the group at the top. She had ditched

The New Yorker guy earlier that morning and now it was just the two

of us.

I recognized one of the three people waiting for us as De

Sheng Tan, whom I had met before through Janet. He was of Chinese ancestry

and as I remember a bit of a smart ass. The other two, a man and a woman

in their mid-fifties, I had never seen before.

“This is Dell and Tory Ames,” she said. “They’re

responsible for the history of the south side of the Pass where we came

up the trail.”

Dell and Tory stepped forward and we shook hands. They were

both solid looking folks, chestnut skin, good hands. Dell wore a blue

baseball hat with yellow lettering that said, “Drill Doctor, The

Drill Bit Sharpener.” Tory wore a blue Dodgers hat, a smile, red-checkered

blouse and Levis. Although they had been married the better part of

thirty years, they looked like they could be brother and sister. Even

their clothes seemed similar, wearing the same kind of boots, making

one wonder who was mimicking who.

“I didn’t expect to see you guys,” Janet

said. “Where’s Myra and Boss?”

“We’re filling in,” Dell said.

“Anniversary,” Tory followed. “They send

their regards.”

“They went on a cruise to Mexico,” Dell ran his

hands into his pockets. “It’s their twenty-fifth wedding anniversary.

They never been to Mexico, so their kids got them a trip and sent them

off.”

After the introductions, Janet nodded to Tory and Dell and

they led us underneath an enormous sandstone overhang that went into

the side of the mountain. Although the trail that brought us to the

overhang was well maintained, the top portion was all poured concrete

with hand railings.

“Pretty fancy,” I commented.

The large opening of the overhang quickly reduced itself

to a tunnel around twelve feet high as we entered. Electrical lights

were fitted along the top.

“We did those last year,” Dell said, pointing

to the fixtures.

“I was the foreman on the job,” Tory backed.

“Got her contractor’s license from that,”

Dell said.

The farther we entered, the more detailings and pictographs

there were on the walls. I thought I saw calligraphy.

Tory and Dell continued onward for a solid five minutes

until we came to a large, dimly lit cavern. Dell flipped a switch and

filled the room with light.

The walls were covered with polychromatic pictographs of

serpentine, mint, orange, red, black and white. Images of the Gerris

remigis, water walker, shared space with twirling suns, criss-crossed

lines, four-legged creatures with long saw-toothed noses. Marine creatures

seem to swim amongst the insect-style compositions, sharing similar

coloration and then switching from orange to green as if changing tense

or part of speech.

Some of the animals were dotted and some were lined. Some

looked like hair combs while others looked like microscopic paramecium,

down to the cilia gyrating around the creature’s circumference.

Several black and orange turtles were present. There were human figures

and iron crosses, even people on horse back. One large, dramatic painting

was obviously a pelican, its wings out, beak high, a sense of forward

motion built into the composition.

“Man, if Sean could see that,” I said. “Knock

out.”

“Validation,” Janet followed. “Isn’t

it.”

“Look here,” Dell walked us over to the walls

beneath the ceiling paintings. “All this,” he pointed. “Chinese.”

The writing was in four groups—square blocks—each

group in eight straight up and down rows of calligraphy.

“Poems,” Tory said. “Homesick Poems of the

Heartbroken.”

Janet knelt, pointing. “I am related to the people that wrote those

poems, Hank. Look here . . .” she translated slowly.

“A flickering lamp keeps me company.

My captain and his boats have not returned.

I have grown old, like a pear blossom tree.

If we should return, spring will be late,

Pity the bare branches that once bloomed."

“And this one,” she moved to the next.

“Is this predestined, that I should lose to gain?

Does heaven say that I will be rich or poor?

Will I be alone or with my family when I die?

Will these dark barbarians be my family?"

“Dark barbarians!” Dell laughed, looking at his

wife. “Are you a dark barbarian?”

“They waited and waited,” Janet continued. “And

the fleets never came back. Two large ships wrecked off the island,

one where the marina is now. They didn’t have room to take everyone

back, assuming that such a large armada from such a powerful kingdom

would return the next year . . . or the next year—or the year after

that.”

“We took them in,” Dell said. “They’re

amongst us,” looking at De Sheng and Janet.

“They gave us words, like `mah’ for horse,”

Tory added. “We had never seen a horse until the fleets came. Look,”

she pointed up to cavern wall. “That is the character for horse

in Chinese.”

“When the Spanish came, we already had a name for horses,”

Dell explained. “We never said `caballo.’ ”

“Is that why I think I see Chinese in the villages

here in the Pass?” I asked.

“Yes, sometimes, for basic things.”

“Like the bathroom,” Tory chuckled.

“Precisely,” Janet continued. “The characters

for male and female. They’re basic and useable. Also, ``up’

and `down.’ ``East, west, north, south.’ ” She pointed

back to the cavern wall. “Here is the pictograph for the sun. Over

here,” she turned ninety degrees, “Is the character for `sun’

in Chinese. Very basic and useable.”

“We share the polychromatic pictograph technique with

the Yokuts and the Chumash,” Dell continued. “But we added

some of the Chinese stuff.”

“We used to use their numbering system,” Tory

explained.

“Right, but Arabic numerals are so much easier,”

Dell laughed, “Hell, even the Japanese and Chinese have switched.”

“And the chickens,” Tory went on. “They come

from the fleets.”

I had seen fancy chickens in the village as well. “With

the cool feathers,” I added.

“Asiatic,” Tory said. “Not European. Zhou

Man left them everywhere. Go to Central America. The Mayans still raise

them. They can’t fly. Had to have been brought here by ship.”

“And good eating,” De Sheng smiled with Dell in

agreement. “They’re pretty yummy.”

“A lot more meat.”

“So where are all the ships?” I asked. “Where’s

the stuff? I understand that they wrecked in a storm, but they didn’t

just melt. What happened to the horses?”

“Come along.”

Dell and Tory led us to the next cave. It was about the

same size but installed with wooden platforms and thick columns of dark

wood.

“You’re right, Hank,” Dell said. “The

storms in 1423 broke the ships up pretty solidly. But they weren’t

made out of balsa wood. They were made out of teak, hard teak from northern

Vietnamese forests, and compartmentalized. So what ever didn’t

break—actually snap—just disengaged like legos. Here,”

he climbed the stairs onto the next level and held on to a post. “All

of this woodworking, these levels and housing, are the rebuilt ships.

This right here,” he held to the post that went floor to ceiling.

“This is called the `Chung-ta-wei’ or the main mast. This,“

he moved to his right, “Is the `Erh-wei,’ or second mast.

All of this wooden flooring is the decks, the transom, the bulk heads.

We helped them retrieve as much of their stuff as possible and brought

it inside where they built places for themselves to live. Eventually,

this all became ceremonial. And the Chinese moved in among us,”

he looked at De Sheng. “Well, some of them did,” they laughed.

“I’m different,” De Sheng smiled. “I

just keep to myself. My father did, too. If you have a radio, baseball

is all you need.”

“Your brothers, on the other hand,” Tory said.

“My sisters have some stories about the Tan brothers.”

“All joking aside, it wasn’t hard for us to live

with the Chinese,” Dell explained. “There were many eunuchs

amongst them—you’ll see this in the Hall of Jars. We didn’t

want their women to go lonely.” More laughter.

“Even though we were so ugly,” De Sheng chided

him. “You took us in.”

“The pulleys,” Janet said. “See the pulleys,

the teak pulleys? My brother Peter found those pulleys in an auction

lot on Ortega Street in Santa Barbara . . . We had to piece this stuff

together.”

“The horses?” I asked.

“Buried. Dead. Drowned,” Dell replied. “As

far as we know, they didn’t make it. And perhaps there weren’t

many horses on the ships that went aground.”

“I’ve heard that there are horse bones out on

Sirenas,” Tory added. “Where some of the Chinese are buried.”

“Where all of us are buried,” Dell added.

“For special holidays,” Janet continued. “We

still use porcelain from the ships. And on Forebear’s Day, called

Ti’at, my father would put on a silken robe that came from the

Chinese. But it’s so delicate now, we just have it to look at.”

Dell looked us over. Janet nodded. “On to the Hall

of Jars.”

We moved out of the cavern and into a broad tunnel. “Janet,”

Dell turned to her while we walked. “You give a pretty good tour

yourself—what with the translations and all. Have you ever thought

about doing the Connected Oral History for any of the caverns or halls?”

“I did a lot of that, Dell, especially before I went

off to school. I keep my mother’s story and my father’s story.

That’s enough sometimes. We just don’t have enough people

coming and going to dedicate ourselves to it full-time.”

“Remember, sweetheart,” Tory told her husband.

“She’s a lawyer. She’s busy keeping the water clean.”

“Well, I guess so,” he said. “But don’t

I have a little filter I put on my kitchen tap for that?”

Janet smiled. “I’m trying to get to the water

before it gets to your tap, Mr. Dell.”

Down the tunnel, we arrived at another large cavern. Tory flipped on

the switch and light filled the space. She joined Dell in front of hundreds

of ceramic jugs and clear jars. Pictographs filled the surface of the

walls. Yellow light shot through the clear glass of the jars and shown

around.

Dell raised a hand. “This is the Hall of Jars.”

“No joking.”.

“It’s really a cave,” Dell explained. “But

we updated the name a while ago. You know, it’s not the 1300s anymore.”

The jars and ceramic containers were set in five to six

levels, a hundred or so across at some spots. The place was well kept,

with fresh flowers and datura placed in orderly fashion. A blank spot

sat prominently amongst the others.

“Junipero Serra’s spot,” Tory said. “We

set it all up expecting the heart to arrive within a day or two of his

death.”

“No slam dunk there.”

“I’m not the main storyteller here,” Dell

said. “Boss and Myra, their two sons, and another couple—Antonio

and his wife, Suluy—they handle much of the COH on this, but since

I’ve been cross-training a bit, I can handle a few stories.”

He pointed, “Since the main heart you’ve heard about is Junipero

Serra’s, one might think that these are all padres’ hearts—but

they’re not. We’ve got some bad Indians up here, too. Some

Shoshone invaders from way back. We’ve got our own criminals who

did stuff within our society from centuries ago. Keeping their hearts

in one place has the same meaning across the board—no afterlife.

With the body not intact, the spirit is restless. A good example in

the news a couple years back, they found Ishi’s brain way down

in the basement of the Smithsonian—”

“Those were Fornay agents,” Janet said to me.

“—Until they brought the brain together with his

body, his spirit could not go on into the afterlife. Did you know,”

Dell continued. “That until then, old Ishi was buried pretty close

to Joe DiMaggio on the other side of San Bruno Mountain in Colma, near

San Francisco. You’re not going to hear that anywhere else on the

planet Earth today.”

He walked up to a line of jars. “We do have Mission

padres here,” he pointed. “Father Gil Y Tobaoda, Mission San

Rafael; Father Juan Amoros, his replacement. Here we have Father Vincente

de Sarria, from Ventura. Not the worst guys, but bad enough. Here, though,”

Dell reached over and clanked the ceramic with his knuckles. Janet and

Tory chuckled. “Two rotten apples, Indian killers. The first one

is Father Jose Maria Mercado who took over at Mission San Rafael. One

day, he armed some mission Indians who went after some visiting folk—probably

just another tribe looking for something to eat or someone to say hi

to—and his people ended up shooting, killing and wounding a good

many of them. Well, we took his heart.

“Then, here,” another knuckle rapped on the ceramics.

“Father Jose Altamira, Mission San Francisco Solana in Sonoma—a

real conniver against his own people as well as a beater, a whipper

and an imprisoner of Indians at his mission. In 1826, they got so fed

up with the man that a band organized themselves and took him on straight

away, forcing him to flee south. His own people hated him so much, that

he wasn’t even allowed back in the system. Then he went off to

Spain. We tried to get to him in the last year he was here—that’s

how bad his reputation was—but missed him. So followed him to Spain.

In fact, it was the son of Sumx Tai Fun, the man who took Serra’s

heart, who went undercover all the way. He removed the heart in Spain

and brought it back to us in the Pass—we were the Israelis before

there were Israelis. Understand? They consulted with us until the Fifties

and Sixties.”

Dell took his hat off and adjusted himself in the heat.

“That’s a great story and you can read it in our main library,

if you like,” he looked at Janet. “Or maybe you can’t?

I can’t remember what’s off limits and what’s not.”

“Maybe someday,” Janet said.

“Maybe

someday,” Dell corrected himself. “Here’s a good one”

over to another group of containers. “The heart of Reverend Stephen

Crumwill, pot hunter, grave robber and inventor of Crumwill’s device.

I understand you went to school with his great, great grandson, Doug?”

“Fatboy” I laughed. “Actually, he killed

the last El Fornio Iguana, too.”

“Well, we wanted his heart as well, but looks like

the so-called Homecoming fire took care of him.”

“Burnt him up,” Tory said.

“To a crisp!” De Sheng exclaimed. “I’m

the one who found him after the flames passed up the canyon.”

“What’re those?” I pointed to other side

of the hall, to little jars and containers.

“Those?” Dell walked over.

“Gonads,” his wife laughed.

“Yeah,” Dell let. “Gonads.”

“Gonads?”

“Yeah, the living Chinese eunuchs and the Chinese eunuchs

that died in the ship wrecks left those behind. The ones who went on

to live the rest of their lives here were buried with their own. But,

the story goes, we couldn’t match the bodies to the jars—you

know a eunuch keeps his nuts with him throughout his life so when he

dies and he’s buried, he can maybe put himself back together again

in the afterlife—we didn’t know what to do with the ones we

saved from the wrecks, so we kept them. Kinda strange, I admit. Like

old cans of paint leftover in the garage.”

“I like to keep my nuts with me my whole life, too,”

I said.

“You don’t even believe in the afterlife,”

Janet nudged.

“Well, if my nuts were cut off in this life I would

have to hope there was an afterlife where, you know, my nuts and I could

be put back together again.”

“I always wonder,” De Sheng piped up. “Would

you keep ‘em on the shelf or in a drawer?”

Dell noticed the light of the phone blinking near the entrance

to the hall. He went over and answered. He spoke for a moment, then

called Janet over. Janet took the receiver and continued the conversation.

“Alright, very good,” she said. “I’ll

tell him.” She hung up.

“What’s up, Jan?” I asked.

“It seems that about ten minutes ago the heart was

returned to the historical society.”

The

Heart is Returned

READ IT!

|