The Pass & Its Geology

from Whole Stole Junipero Serra’s Heart in a Jar?

A Chronicle of the Founder of the California Missions Lost TickerBy John Graham

Here author John Graham describes the geology of the Pass, the huge sandstone construct of mountain and caves that rises above the town of El Fornio.

“The trail wove through the red, purple dirt of the Sespe. Blue belly lizards shot ahead, stopping to look back, only to dart further along before disappearing into the short, turpinoid scrub. Every so often a stand of weathered sandstone stood collected with shoots of bonsai manzanita, juvenile oaks, grasses and succulent chalk dudleyas adorning the cracks in the red and black weathered cream surface. After some consideration, one realized that the sandstone pilings—weighing many tons—were not outcroppings but piles of stones that have split from the upper ridges centuries ago, rolling down the mountain to a final stop where wind and rain smoothed the corners and burled knobs.”— “Sandstone Pilings”

from 144 Vignettes About El Fornio, CAAbove the town of El Fornio, California stands a huge sandstone complex of caves and canyons. Through the centuries, the Fornay Indians developed these formations into a huge system of dwellings that dwarf the once-inhabited caves of Pueblo, Colorado as well as other known cave cities in the Old World. The area is simply called “The Pass” and the Fornay Indians have made it their home for centuries.

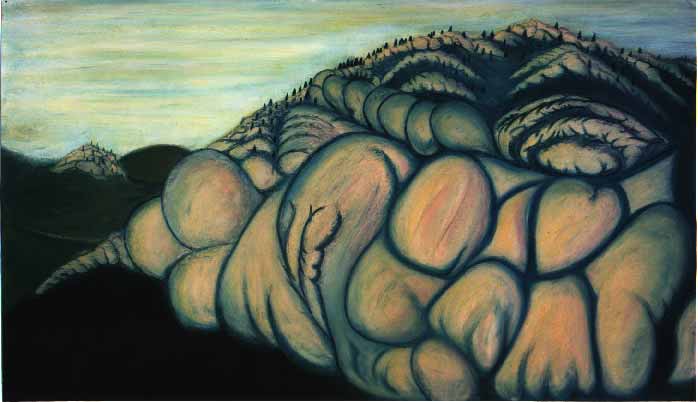

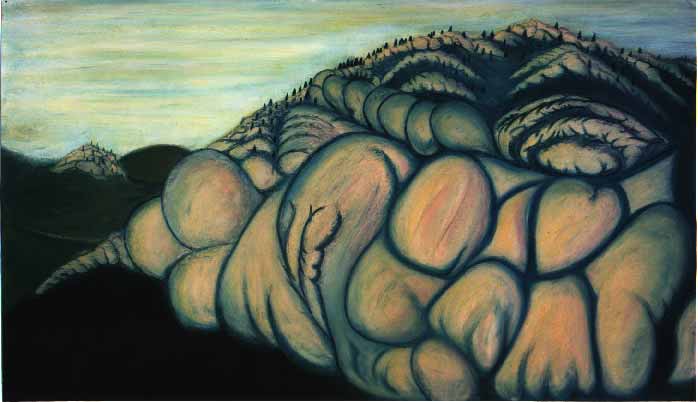

The Pass stands 3,985 feet from sea level. This distance, its highest point, is the peak of the giant sandstone face that can be seen looking east from city streets. It is blond in the high sun, with tints of pink at the edges caused by lichen. This two thousand foot rock face is not flat but seems to be made of uneven, gigantic pillows—hundreds of square yards in area—fit tightly together to make up the surface. This is the natural wear on what had been an ocean floor, worn down through millions of years. The precipice is supported by a thousand odd feet of green chaparral wormed with trails and hedges, the natural boundaries of Fornay land foothills, houses and neighborhoods begin.

But a natural boundary isn’t enough.

“Our ancestors fought back a lot of comers through the years,” Peter Librado, a one-time journalist and now leader of the Fornay, says. “It was as if we were practicing for the arrival of the Europeans.”

Beginning in the 1920s, the Fornay began putting up fences around the entire one hundred and twenty mile perimeter of the Pass—some of them electrified. At points along the fence, sentries sit in eight hour shifts, often armed, uniformed, and equipped with radios (not to mention medical and retirement benefits). This defensive barrier isn’t so much the result of military paranoia rather the history and Jeffersonian discipline of vigilance.

Through the centuries, invading tribes have tried their hand at making it to the top of the Pass. Like Romans seeking to topple the Basques, intruders were met with hails of boulders and projectiles. As the area is laden with hidden caves, Fornay warriors could suddenly appear offering arrows and springing traps unseen by their aggressors before disappearing, literally, back into the land.

The Spanish learned to respect this defense quickly, as did the Mexicans who came later and then the Yankee curious who attempted to bully their way up. Nowadays, the sentries were mainly there to discourage curious kids and well-meaning sightseers who tried to find their way up the switch-back trails that lined the sides of the mountain. The 1960s and early 1970s found many an LSD- or psylocybin-laced flower child wandering the lower slopes looking for entry, only to be gently turned away and sent back down the mountain.

The rock of the Pass was formed roughly 55 million years ago during the Eocene epoch. The Eocene was part of the division of epochs that made up the Tertiary Period of the Cenozoic Era. During this time, the dinosaurs were long gone and the larger mammals began to appear, like camels, horses and even monkeys. Grasses and grains were developing.

Four basic kinds of this Eocene-bred rock made up the Pass, from bottom to top. Most of this rock was formed from the in-land run off of minerals pouring into the ancient Pacific. The layers hardened, rose and through association with plate tectonics were heaved upwards, their eastern edges turning west, until they were not only pointing straight up, but actually tilting all the way back, at twenty-four degrees west, as if the layers were limbo dancers bending back.

At the foot of the Pass was the Sespe. This rich, brown rock can be found first in the trails leading up to the Pass. While the other rock formations that make up the Pass are oceanic, the Sespe is of continental origin. It is run-off that largely never made it to the ocean floor. It can be found as far south as Malibu where it comes right down to Highway 1 as the road winds along the side of beach houses. The Sespe is full of cobblestones and a red sediment of oxidized iron and river rocks that have traveled from as far away as the Colorado desert. To stand in front of a cliff of purple Sespe—to see it six feet from the car window—full of cobbles and detritus, is to look at a geologic moment frozen in time. As individual stones fall from the formation throughout the year, they pass from one geologic age to another.

The second rock, the base of the “blond” colored mountain, is Coldwater Sandstone. In appearance, it would seem to be nearly the same as the Matilija Sandstone that makes up the top of the Pass. And like Matilija, it is made of ground down and dusted granite sand, washed into the ocean to form large and deep sandy bottoms during the Eocene. At this time, the waters were warm and brackish, potentially life supporting. Therefore, fossilized oyster beds can be found in the Coldwater formation of this part of the Pass.

The third type of rock is the much softer and appropriately named Cozy Dell Shale. Formed in the upper Eocene approximately thirty-five to forty million years ago, Cozy Dell Shale is just that—shale. It is gray matter, fine mud, not the sandy bottom of the granite-type run-off that is sandstone. It is the hard mineral portion of what becomes a pocket of oil. Shale is the dead bones, calcium, and methane, stinky dead stuff, of all the organisms that sunk to the bottom of ancient water bodies. It crumbles easily and erodes in wind and rain much quicker than its sandstone neighbors. Because of this, saddles of Cozy Dell, sitting between harder sandstone, can be completely dug out, leaving deep pools of water book-ended by sandstone formations. The Fornay took advantage of this in the Pass where even larger pools were dug out by hand and tool to create both open and topped-off cisterns.

The fourth and final type of rock that finished the top of the Pass is Matilija Sandstone (“matilija” is a Chumash Indian place name whose word origin is unknown). It is white to blond, sometimes gray, weathering to a cream color and highly resistant to erosion. The Matilija was laid down in the later Eocene, a granite sand spread over the floor of the ocean in a near even blanket. It contains no fossils as the marine environment at the time was much colder.

After these old ocean bottoms dried out and were thrust up to become mountains, wind and water blew through them. Eventually the Pass was formed, with its natural caves and springs. When the Fornay Indians arrived —whatever cultural form they were at the time—they likely encountered animals living in the Pass who used the caves for shelter—bears, bats, mountain lions, owls, perhaps even sabre tooth tigers. At some point in their settling of the area, a sect of the Fornay remained permanently in the canyons and corridors of the mountain. Although they originally utilized the entire outlying low lands and beaches—obviously County Corner’s original designation as a Fornay territorial cairn can’t be dismissed, and Sirenas Island as the tribal burial ground and their connection and dependence on the sea is well established—the Pass always remained the one place of dependable retreat.

This geologic anomaly is unique from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego and defines the life and security—the story—of the people who happened upon and fashioned it into the pre-Columbian condo-complex it became.

In this photo from the late 19th century, four generations of Formay Indians stand at the edge of one of their "canyon caves," lined up in their Sunday best