At

least, that’s how I imagined it happening—the theft

of the heart. To be honest, that’s how I wrote it. As

the curator of the El Fornio Historical Society and a trained

archeologist, I had taken the amateur historian part of my

career and hitched it to my nearly legitimate career as a

curator.

That’s how I became a fiction writer.

As a side project I had been writing an account

of Father Junipero Serra’s heart

as it chugged its way through California history. Actually,

I kind of had to write it because my “cousin” was

discouraged by my lack of interest in the subject. As the

curator of the historical society—and a close friend

of the local Indian tribe—I was, in her opinion,www.multiluxury.com in a

position to be more empathetic to the tribe’s interest

in the heart. So I began the story six months ago, beginning

the narrative in 1789, the day the old boy’s heart was

taken from his unwarming corpse, slipped into a ceramic jug

filled with brandy, and rode away on horseback.

Believe me, I have been completely realistic

about the difficulties of writing a book—especially about

the marinated heart of a Spanish padre. Even if it turned

out to be any good, “The History of Junipero Serra’s

Heart in a Jar,” conceived without a single car chase

scene or radio pop anthem, seemed at best a gentleman’s

pursuit, a stoned idiot’s collection of doodles writ

upon a dozen moleskins.

I often thought of just dumping all the research

into a lightly written travel guide. I already had all the

pictures and text.

A Drive Down 101 was my working title.

You see that kind of fluff all the time in the bookstores.

Recipes from the California Missions or Great Hidden

Trails in Your Own Backyard, Vol. 4 (which aren’t

hidden anymore if you write about them.) Somebody was making

a career out of this stuff. So I, of course, asked the question

that shouldn’t be asked: Why wasn’t I doing it?

I mean, why sweat the literary thing when I could just plug

the whole project into captions and photos?

Collecting the necessary flotsam to write a book

made me no different than anyone else in the state. Throw

that many half-educated people into one society and they’re

all going to think they have a book to write. Some even get

around to doing it— then one day when they walk away

from it, their kids find tomes-in-drawers next to half-loaded

revolvers.

Which I didn’t want.

So I decided to take a serious stab at my cousin’s

proposal to write about the heart because—until it was

stolen—she was right: I barely noticed it.

Maybe it was because it got lost in all the other

bric-a-brac the previous curators had collected over the years.

I only saw my own collections, my own point of view of history

through the historical society. For my cousin, who was part

Indian, the heart in the jar was like a rosetta stone amongst

bricks and mortar. For me, it was like a another pinpall machine

with a theme—and I wasn’t really into the theme.

At least not at the time.

Except for Junipero Serra’a heart in a jar,

The El Fornio Historical Society was no different than any

other historical society in the state. We had a collection

of Indian things and European things. The Indian things we

had, the artifacts to be professional about it, were

objects the local Fornay Indians hadn’t managed to reclaim

through the dozen or so court orders issued through the decades.

We had your usual grinding stones, arrowheads, bone flutes

and needles. Nothing particularly special.

Technically, the Native American stuff we had

was here because it was never assigned to any particular tribe.

We all knew the collection was Fornay—everybody did—but

by never designating it, the historical society was able to

hold on to the modest collection it did have. It was territorial

pissings enough that we had Serra’s heart in the jar.

The Indians so wanted it but knew—by an agreement going

back to 1926—that if the heart stood under the roof of

the historical society, it was our’s. But there will

always be plenty of time. The afternoon the grail was walked

out of the building, a big game of grown-up finders-keepers

was under way.

I was in my office that day, upstairs, a Friday,

scribbling away about the holy pumper’s narrative, circa

1876, trying to focus my writing of the book against the backdrop

of the week-long Old Spanish day festival getting started

outside. Even a dedicated bachelor scholar like myself, playing

Mr. Writer, had to throw in the towel. Three skyrockets shot

by the window and burst their innards against the glass

(laiizez faire El Fornio had never outlawed the blasters—too

many Chinese and Indians . . . Mexican and Irish, Japanese,

Croatians—you name it.)

Figuring why be burned alive in an old wooden

Victorian full of dusty jars of formaldehyde, I stopped writing,

cleaned up, and went out for a drink. Was the back door locked?

Was it not locked?

I wondered.

The whole town was about to descend into its

annual ritual of smokey barbeque, horsey parade and drunken

revelry—not an afternoon that seemed like someone would

sneak in and take an old padre’s pickled heart.

My name is John Peabody—John

Henry Peabody. Like Robert Plant shouting, “John

Bonham! John Henry Bonham!” at Zeppelin’s

`75 Madison Square Garden show.

But not.

For the most part, people called me Hank. I don’t

even look like Robert Plant. My hair was dark, when I had

it. My beard was scruff but trim to balance the strandy pate

I mentioned growing above my eyebrows.

As for Peabody being my last name, it pretty

much summed me up as a boy, second-string linebacker-type,

resilient, but continually knocked on my ass by the larger

guys. In baseball, I loved playing catcher, even as the gear

quietly suffocated me. I could do it, sure—but a throw

to second base usually ended up in the back of my head, between

my hair and the straps, the mask, shin guards and chest protector

pulling me to Earth.

It was only through much concentration, steak-eating,

beer drinking, body surfing, trailblazing and what passed,

in my case, for girl chasing, that I made it to five feet

nine inches tall (it was probably eight, but I kept with the

nine, anyway).

Half way through college, I was more body than

pea, finally.

I’ve now been the curator of the El Fornio

Historical Society for the last two years. My specialty was

Native American coprolites—from the Greek, “dung

stone”—which, yes, made me a high-falluting shit

collector.

My science was collecting poop from people who

had been dead for hundreds to thousands of years. I examined

poop so that others might know something about dead people

and what they pooped when they pooped it.

The Neverending Poop, I called it. While not

exactly as fossilized as dinosaur remains, the term’s

origin, the ancient scat I relished was nearly always dried

to perfection, just waiting for me to come along, manipulate

and catalog it.

Catalog?

As you can imagine, being an expert on Native

American coprolites was a real panty dropper. Take a girl

back to your place and see how she reacted to that esoteric

specialty. Maybe that was why I have been single for the better

part of a decade. One person’s scientific specialty was

another person’s gag reflex. While a lot of people could

take the ladies to their den and show them arrowheads and

mysterious shamanic totems, all I had was a vast and well-footnoted

collection of dried up indigenous litter with which to hypnotize

the local mädchen. As Spongue Bob Square Pants once said,

“Good luck with that!”

Yeah.

I was born in El Fornio, California in March

of 1962. I was one of those fishy Pisces let loose along the

California coast, just south of San Luis Obispo and north

of Santa Barbara. I went to El Fornio High School—where

I was a Moor—and got both my undergrad and graduate degrees

from the University of California at Santa Barbara, where

I was a Gaucho. My mother, Elizabeth McCandy Peabody, from

Nebraska, lived until I was twelve years old when she was

killed in a car accident with the mother of a school friend

of mine. My father, the well-known and occasionally disparaged

California ethnologist, Francis Henry Peabody, PhD., died

after my fifth birthday.

A trained linguist and ethnologist, old “FHP,”

as he signed his name, documented the vanishing languages

and cultures of California Indians throughout the 1920s to

the late 1950s. Some two thousand wax cylinders and magnetic

tapes of Southwestern and California Indian languages are

attributed to his fieldwork. Completely dedicated to his career,

to the point of eccentricity, it has been generally accepted

that Francis Henry Peabody—my old man—went a bit

“native” at the end of his life.

In a notorious front page, lower left (or second

section top right) news story—depending upon the paper

you read—Dr. Frank Peabody died at the home of the Saticoy

sisters, Linda and Hermosilla, Central coast Indians whose

mother was one of my father’s original informants. He

was found in a sweathouse built out back of the sisters’

white Victorian, dressed in a loin cloth with shell beads

and stone fetishes hung from his neck.

A formal man who wore slacks and a blazer everywhere

he went—even into the field—Frank Peabody had stopped

shaving in the last year of his life, given to wearing native

costume and body markings in pursuit of what I’m assuming

to be his final anthropologic quarry. Although the coroner’s

records say he died of a heart attack—which at eighty-one

years old, raised on an early twentieth century American diet,

was not surprising—most accounts suggest that the night

of his death my pops was pretty high on datura or toalache,

the Indian psychoactive used in religious rituals for centuries.

However you want to think about it, my father took his work

seriously. How many white guys of his generation died like

that?

When I signed on to the job of director and curator

of the El Fornio Historical Society, I had some pretty clear

intentions. Although I had only met my father once—when

I was five (I don’t remember it)—I was determined

in some hazy way to continue his work, aside from the loincloth

get-up.

After ten years in Santa Barbara and Ventura,

doing Environmental Impact Reports for the county as well

as archeology for private firms like James & Doore, Native

Reclamation, and Malibu Flute Expansions, I had seen my career

get completely sidetracked. Every time a movie guy in Montecito

put a hot tub or putting green in his back yard, they would

call me in. I’d sit there, chewing gum, drinking Dr.

Pepper, waiting for the backhoe to dig up some ancient local.

On site with me would be an NA, or Native American—sometimes

called a CLR or “Closest Living Relative.” One thing

NAs were good for, I always said, was gum, soda and menthol

cigarettes, most of which I never imbibed in. But once in

awhile, your career in the shits, a couple of sticks of gum

and a Dr. Pepper were the only things between you, a cigarette

and oblivion.

I always had a studious eye pealed for my specialty.

The occasional short log stuck in the dirt—almond roca

from 236 A.D.—shined to me like a Spanish coin. Mostly

when you worked county and private firms, you paid attention

for ribs and kilter, skull caps and shell, ash, dust, people

stuff that suddenly presented itself under the weeds. I knew

ancient log like no one.

In 1991, after mostly finishing my dissertation

at the University on “Central Coast Native American Coprolite

Densities,” then putting in a few odd years of EIRs,

I could definitely say my career was twice as shitty as when

it began.

In those days, I would apply for assistant curator

positions at places like The

Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History or Director of

Archaeology at the Channel Islands Historical Society.

No luck. Once I applied to be curator at the

Goleta Train Museum (I liked trains well enough),

but eventually I just couldn’t bare the thought of driving

a miniature locomotive around for kids on weekends, dressed

in overalls and a conductor’s hat. I also realized that

after years working the area, Santa Barbara had its own caveats.

There was only one of anything in town. So once you were it,

that was it. If you weren’t anymore, you weren’t

it—and you could never be it again. Since I had never

even been it once, I was happy to get my stuff and go.

To be honest, it was pretty clear that no one

was interested in an expert on dried turds, even if they were

Native American turds—and it wasn’t like I wasn’t

invested. I was prepared to donate my Central Coast coprolite

collection to any one of the institutions I had applied to.

They were nice display cases, real glass and

mahogany (how much is real glass and mahogany anymore?). Most

people didn’t even know they were looking at dried scheiss

unless you told them. They just figured they were gazing at

important artifacts—which they were. Whole families placed

their hands on the wooden and glass cases and went, “Wow!”

while gazing at my work.

The afternoon that Serra’s heart was taken

from the historical society—also known as my office—I

imagined, and was pretty sure, that the heart and its liberateur

headed out of the building and in the direction of the growing

party. Together they would have eyed the wooden stalls of

tamales, olive oil, T-shirts, cheeses, lettuce, tri-trip sticks,

wheat grass shots, and Bear Republic flags on margaritas.

The old padre’s carburetor passed the apple-smoked

sausage and chorizo stall put on by the local Jaycees. It

floated by the century old Aliso-Kennedy

brand tomatillo salsa booth. Through the streams of Friday

night festival-goers, the heart made its way up the avenue

in rhythm with the bandit’s stride. Together they passed

children in red, yellow, black and green uniforms, dresses

and vests ironed for the parade now a bit unbuttoned and wanting

to go home, to play with friends . . . A skyrocket whistled

into the air from behind a fence and beer bottles broke with

drunken laughter as the rocket cracked, sending sparks flying

all around. A man in a pelican costume sauntered waist-high

amongst the crowd. He waved to the crew on the patio at the

Rusty Pelican, deep into their fourth round of Rob Roys where

a band clanged out a hazardous version of “Walk Don’t

Run.”

“Hey, Sean!” one of them leaned over

the rail, waving.

Sean Heany, music

critic for the local “Daily Breeze” paper, pelican

mascot around town, shorter than anyone you’ve ever seen

and a man worth knowing, was making his Friday late afternoon,

early evening rounds.

“Keep it up, Heany,” I toted.

Sean saw me and nodded with a knowing Heany scowl.

Everyone had shown up for an Old Spanish Days inoculation

and Sean was ready to administer it. That’s what he did.

The pelican spiraled his arms with the feather

coverings of his proxy wings. “This should keep everything

cool,” he said, feathers fluttering in the dusky heat.

The crowd cheered him.

I knew that I would be back to the Rusty Pelican

in the next hour or so, but right now I had to walk through

the droves, conducting my annual stroll down Main Street to

see just how dazzled everyone was getting. And Dazzled was

what they got on Old Spanish Days (also known to the locals

as “Old Spicked Out Gays”).

Every year, in the first week of August, the

town threw its annual festival, drawing tourists up and down

the coast in the hopes that they would spend their time on

paper cups, plastic hats, grilled fauna and the narrative

fantasies of adjacent history.

Protesters to the event claimed the scene to

be “White people dressed up like the Mexicans they displaced,

dancing on the graves of the Indians,” which was kind

of true. But a lot people at the annual festival were rich

in melanin and a lot of Indians who lived up in the Pass had

never died, and some people, the tour guides proclaimed—cameras

flashing—were “dressed in the manner of the great

days of the Spanish Californios, right down to the

silver belt buckles.”

Whatever. Everybody had their own story to tell,

but any attempt to define the area was always incomplete as

it was a slippery business to begin with—born out of

a slippery history. Just as winter mudslides had continually

changed the topography of the adolescent geology, a moving

in and out of peoples had continually changed the face of

the locals. After picking up everybody’s shit for the

last two thousand years, I liked to think that I had a pretty

good picture of who everybody was around here. Only later

did I find that I only had an inkling.

In my case, I had always thought of myself as

a teenager in permanent state of wonder. I think you need

that to be in my profession. In fact, you needed it to be

Me. I had spent so much time wondering about the deaths of

my mother and father that wonder became a state of being.

I wondered what it would have been like to grow up with my

father. I wondered what it would have been like if my mother

wasn’t killed in an accident. I wondered if anyone was

going to figure out that I had never, technically, finished

my degree.

I just plain wondered.

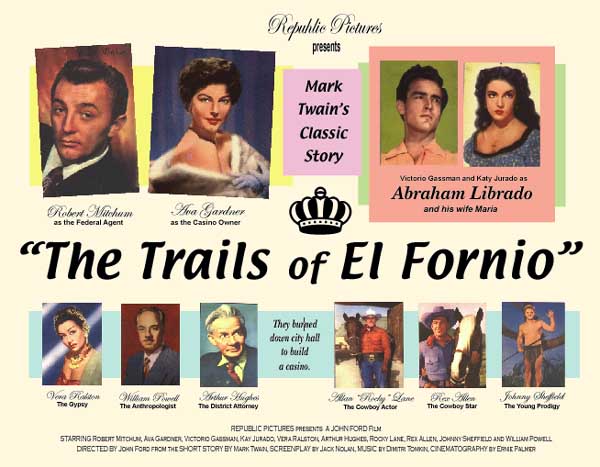

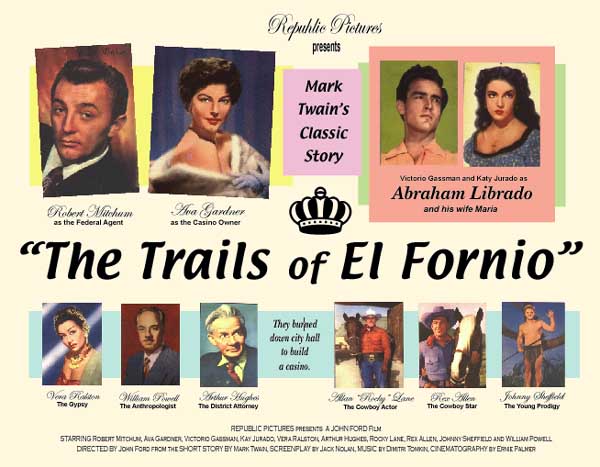

My wondering could get the best of me. The Hollywood

director, John Ford, who directed Mitchum and Ava Gardner

in Mark Twain’s “The Trails

of El Fornio,” knew about my father’s work through

his relationship with the Indians he had been casting—and

shooting off of horseback— for years.

In “Trails,” he cast William Powell

as “The Anthropologist,” which was a nod to my old

man. In some of the scenes shot in downtown El Fornio, you

can see my father standing in a crowd listening to the actor

Victorio Gassman, portraying the great Abraham Librado, chief

of the Fornay for most of the twentieth century.

In these scenes, my father was tallish, thin,

dressed in ill-fitting trousers and a blazer looking slightly

unfocused. Powell, portraying my father, stands in the foreground.

The look on my father’s face, ever the observer, seemed

to be saying how lost he was standing in a fiction, looking

at the man he was being portrayed by, while at the same time

being himself looking at the people he knew to be real set

amongst all the actors. My father, from what I heard of him,

made his career getting at the core of a person’s nature,

their narrative. Movie-making, as much as he might have appreciated

it, was one, even two steps back from the reality he was after

. . . These thirty seconds of him shifting and blinking his

eyes as a movie extra were the only animated record I have

of my father. I am the only person in the world that knows

that I watch this scene four or five times a year. And if

I have enough beers in me, I wonder until the tears run down

my face.