Listen

to voice over artist Tim George

read

the part of Hank Peabody

Visit

Tim George's website to learn more

about his work

www.timgeorgevo.com

Lenses, Hearts and Rockets

from The Reeducation of a Turd Peddler

by John Henry Peabody

WHEREIN HANK

IS BROUGHT UP TO THE PASS

BY JANET, ON THE WAY TO THE HALL OF JARS,

AND SPENDS TIME WITH THREE RETIRED

FORNAY INDIAN GENTLEMEN.

THE

FORNAY HAD BEEN GRINDING LENSES for nearly five centuries. The local

sandstone—both Matilija and Coldwater that made up the

Pass—was riven with lodes of crystal structure.

Longer than anyone can remember, the Fornay had coveted

and polished the crystal chunks into the charm stones and amulets discovered

by anthropologists and pot hunters to this day. I do remember once in

high school when Fatboy Crumwill showed

up in the parking lot with a trunk load of this kind of thing and I

thought, “You are just asking for trouble, brother.” He didn’t

care. His family had done that kind of thing in the area for two centuries.

Crystals were unique amongst rocks. To ancient peoples,

an old Fornay explained to me, crystals were like frozen water, but

they never melted and they weren’t cold. They could sit in the

sun all day, hot and unmelting.

In the hierarchy of materials, crystal was the wise man’s

stone. The hunter had obsidian—black, igneous, quickly drying magma

glass—and he had chert, Franciscan, pure and brown as chocolate,

or white, Monterey, striated with black and blue. Each was capable of

being knapped into a razor. But the Shaman had enormous and peculiar

bits of crystal to make magic rocks, crystal balls, and heads of staphs

into which they could see. If the clarity of the deposit was good enough,

a shaman could look into a crystal, even before polishing, and see worlds

that had been hidden and waiting for discovery. A holy man in Nevada,

in 1045, looked into a large geode with its crystal center and saw a

mushroom cloud set slightly back, rising towards the frame of the geode’s

proscenium.

By about 1300 A.D., the practice of shining crystals fell

out of the hands of the shamans. A fraternal cult developed around the

use of crystals, not unlike the sororities of basket makers or fraternities

of tomol plank canoe makers encountered by Cabrillo at Carpinteria,

near present day Santa Barbara.

Weeks were spent buffing the best rocks with chamois-style

deerskin and grades of sand. A well-polished piece of crystal could

be used for ceremony, to astonish the citizenry or start a fire. A lense

of crystal given to a boy or girl would magnify a captured bug—or

grill a desperate ant with the sun’s rays. Crystal set in boxes

held blue caterpillars glowing in the summer night to light a traveler’s

way up the Pass.

Zhou Man’s armada had been using telescopes throughout

their voyage. When they arrived in El Fornio, one of the first things

that the Fornay took to was the Chinese use of the telescope. After

the beaching of some of their ships in early winter, 1423, they offered

their skills to the Fornay—one of which was the development of

visual lenses.

In 1784, when J’Topet, the Salinaan Indian, sat on

his belly at the Valley of the Bears peering through an “eye stick”

provided by Muhu and Monsow—as they looked for Junipero Serra’s

heart—he was looking through three-hundred and fifty years of shared

Fornay and Chinese technology.

No small wonder a dozen Fornay men and women went on to

attend Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in the 1940s and 50s, the “other

MIT,” applying their interest and know-how in lense technology.

The team that put together the Hubble Telescope, with its concept of

analog lenses and digital relay communication, had two Fornay Indians

on their roster—one a descendant of Sumx Tai Fun, the procurer

of Junipero Serra’s heart, and his brother, Muhu “Owl”

Tai Fun, who provided J’Topet his first look into a Fornay eye

stick.

Today, strung along the highest points of the Pass, the

Fornay have state-of-the art telescopes. Although the modern scopes

were purchased from outside, many children are still taught how to make

the kind of eye stick the Chinese helped the Fornay develop.

The “Gaan Geng Festival” or “Lense Festival”

takes place once a year at the summer solstice. Grandparents work with

their grandchildren to make imaginative to highly functional telescopes

using only allowed materials. Because of this tradition, discussion

and use of the telescope are a favorite pastime. Even local Walgreen’s

are required to carry at least two kinds of telescopes as part of their

neighborhood contracts.

As part of my “education,” after the theft of

the heart, Janet arranged for me to head up into the Pass and meet some

of the Fornay.

The very first day we hiked up to the forward point of the

western face of the Pass with a journalist from The New Yorker.

Janet was showing him around, so she left me there, about two-thousand

feet up, facing the Pacific, while she took her guest down into the

villages on the eastern side of the crest.

I was given three retired Fornay gentleman who were drinking

tea, reading the paper and looking about the area with a Celestron C80Ed-R

telescope—not that I knew that, but that they were happy tell me

all about it.

The sky was clear, a mild front having passed through and

run off the fog of the previous day. Across the channel one could see

the Island of Sirenas. Something, likely dolphins or an upwelling of

anchovies, was working the surface a mile or so off shore. The sun had

about forty minutes left above the horizon. The blues were turning to

orange. Soon the oranges would turn to yellow, and white would flare

off the water as the horizon cut up into the sun.

The three gentleman, two of whom I had seen around town,

offered me some of their tea as they fooled around with the telecope.

“All I know is I didn’t steal the damn heart,”

Benny, in his fifties, eight years retired from PG & E, said.

“Oh, they’ll try and peg it on an Indian,”

his brother-in-law Charlie went on. Charlie had been a Prudential Life

Insurance guy for years before taking over the reigns of treasurer for

the tribe. He retired three years ago.

“I think it’s a good opportunity now,” Sy

said. Sy had been a schoolteacher and served on the downtown Board of

Supervisors in the early 1980s. “I think this is our chance to

get it back. Whoever stole it has loosened it up for us.”

Charlie was looking down into the neighborhoods. “Let’s see,

what do we have?”

Sy and Benny laughed. “You dirty old man.”

“That’s the Chinese for you. You’re all so

hard up.” They laughed at Charlie. Charlie was Zhou Man—meaning,

like Janet, he was descended from the Chinese explorers.

“Hey, don’t tell me you haven’t done it.”

“No,” Sy said. “But I’ve been told that

the time to do it is not at a quarter to five in the afternoon. You

have to wait until everyone gets home from work. Then they’re changing

their clothes.”

They all howled.

“Here,” Benny redirected Charlie. “This is

a great time of the day to see County Corner.” He swung Charlie

around and pointed the telescope north. “At this time of year and

this time of day, you can actually see the shadow cast by the post.”

“Nah,” he drawled. “You lie.”

“Yeah. I’ve seen it. Let me show you.” Benny

took the telescope and directed it north, towards County

Corner, where “The Oldest Standing Fence Post in the West”

was situated.

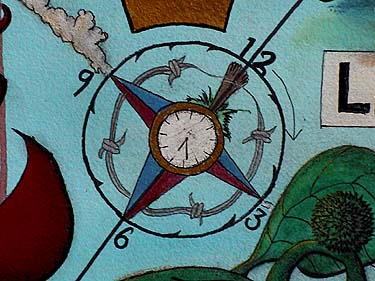

The orginal County

Corner fencepost, on display in

the garden out front of the historical soceity.

For

centuries, before it was a fence post, it had been a Fornay rock cairn,

denoting the northern edge of Fornay land. When the Spanish began surveying

the area, high ground and rock cairns were some of the places they started.

The rocks at County Corner were kicked over and scattered years ago

by Spanish boots and sandals, but its place as the transition between

native presence and European ownership was solid.

In 1926, the original fence post was replaced by a clean

piece of four-squared, milled wood which stands there today, while the

original post leans in a reliquary at the historical society (about

twelve feet from where Junipero Serra’s heart sat).

Today people go to County Corner to have their picture taken with their

aunts and uncles and other out-of-towners. You can buy a hotdog and

a coke there, too, if you want, a bag of chips or an ice cream cone.

While most of these people don’t do it, I like to remember

that standing with the post, one is tracing the bodies of those who

came before them, putting their body where ancient bodies stood. This

is particularly true if one followed the measurements away from County

Corner as a spot of survey. Any sub-division or road measured from County

Corner was a reference to the area’s historical body, its corner.

Flat on a mattress in a room in a modern house, you have been put there

by County Corner. Laying in bed facing the Corner, you’re on the

grid. You’re a compass. Driving in a car, laid out on local roads,

you are in reference to County Corner. You see it: when my mother and

Janet’s mother were killed in their automobile accident, it, too,

was a reference to County Corner.

“There. See,” Benny left the telescope and directed

Sy over to look.

“If you ask me,” Charlie said. “Whoever took

the heart has to have a reason to want it.”

“We didn’t do that job,” Benny said to him.

“We had other chances. But that would’ve been too obvious.”

Sy kept looking through the lense. “Oh, yeah. There

it is. You can see it.” He waved Charlie over.

“Alright, alright,” Charlie skittered over and

looked through the telescope. “Technically, my County Corner is

about eight thousand miles that way,” he pointed west across the

water.

The other two scolded him. “Traitor!”

“But, yeah,” he stared through the lense. “You

can see the shadow. That’s a good trick, Benny,” he gazed

for a moment and then relinquished the telescope.

“Hey, shit collector man, you wanna have a look?”

“No,” I waved them off. “I’m just here

to watch.”

They shrugged and started back into themselves.

“If you wanna know what I think,” Sy said to them.

“I think it’s either one of two things. It’s either some

kids thought it was funny to steal it, and that means it’ll turn

up in a bar or fraternity somewhere, or some big time ass hole wants

to make a statement.”

“Like those canonization people,” Charlie offered.

“Maybe they want to get a hold of it and, I dunno . . .”

“You’re on there, Charlie,” Benny let in.

“This `Society to Do Whatever the Hell It is They Want,’ ”

he waved a hand trying to finish his sentence. “What’re they

called?”

“The society that wants to be a bunch of assholes is

what they’re called,” Sy finished. “You know, rebuild

the mission and sell ice cream cones.”

“Yeah,” Benny pointed. “They could do it.”

“Well,” Sy figured. “The whole group? I don’t

think so.”

“Alright,” Charlie looked at his watch. “The

real reason to be up here,” he readjusted the telescope. “Not

that shooting the shit with you old duffs and hanging out with, what’s

your name again?” they asked me.

“Hank.”

“Yeah. The historical society guy—you’ll

like this,” he looked at me. “This is the science part.”

Charlie hit his watch again. “I’d say about a minute.”

They followed him as he spun the telescope around and pointed

it south. Then they all looked at their watches.

“5:58,” said Charlie.

Like a single bird alighting, a small white flare of an

object started straight for the sky. It headed up steeply, leaving the

faintest contrail and no sense of shape or depth.

“There she blows,” Charlie smiled. “A Lariat

heading for the other side of the planet.”

“Kapowey,” Sy let.

“Ka-ching,” Benny backed him as they watched the

object race higher and higher into the atmosphere.

It was a Lariat Missile out

of Vandenburg Air Force base to the south.

We watched for about a minute and a half before the missile

disappeared into the atmosphere, its contrail leaving a flush of emerald

and orange whisp.

“Well, that’s that,” Charlie looked around.

“Yeah,” Sy kept his eyes to the sky, watching

the contrail unfold, going into blues and reds, a silver shimmer passing

through.

“Ain’t it perty,” Benny said. “That’s

some napalm they got there.”

“So, Harry,” Charlie said. “Is Ms. Janet

going to come back and get you? Or are we just stuck with you for the

rest of the evening?”

|